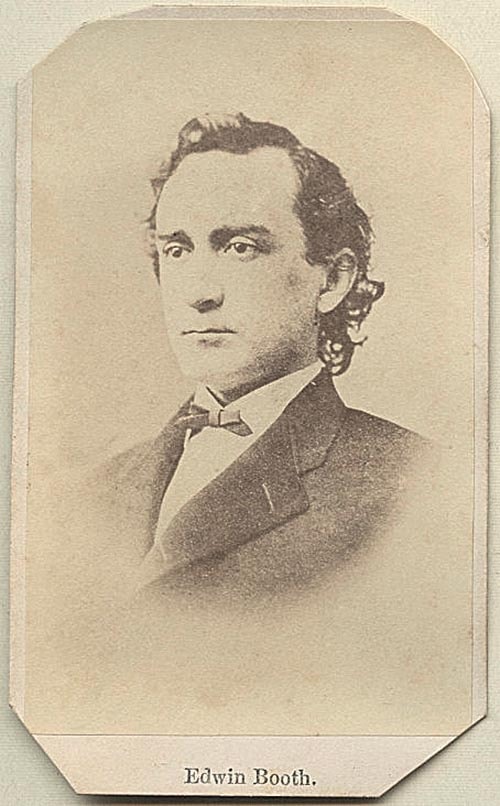

There seems to be a ghost in the room. “I can say his name if I want to—John Wilkes Booth!” cries theatremaker Cynthia von Buhler, standing next to Edwin Booth’s bed, where the great 19th-century actor died. There is a lit candle next to the bed, and a photograph of that other Booth above it. Folklore has it that Edwin forbade people from speaking his notorious brother’s name in his house. Von Buhler likes to defy superstition.

“John Wilkes Booth!” The candle goes out, then abruptly lights up again. Von Buhler jumps back in apparent alarm. “Ah, did you see that?” The lesson here: Don’t challenge ghosts.

Like most things that happen during a play, this supernatural moment was orchestrated. “I do a little magic—wasn’t that good?” von Buhler confides, giggling, a few days after. Even if the candle in Edwin Booth’s bedroom was rigged, there’s no denying that there’s something eerie about entering that top-floor sanctum in the Players Club, an ornate, history-soaked residence that faces onto midtown Manhattan’s Gramercy Park. Nothing has been changed or moved since Booth died in that room—not the red fabric of the bedspread, not his pipe collection next to the window, not his slippers lined up just so next to his bed. For years after his death, whenever a Players Club member would ask for a key to his bedroom, the attendant would warn, “Don’t wake up Mr. Booth.”

And von Buhler’s play Speakeasy Dollhouse: Brothers Booth, currently running at the Players Club on the first Saturday of every month, makes use of three floors of Edwin Booth’s former residence, using it as the stage of an immersive play in which audiences can follow characters around and talk to them, and in which every room is buzzing with activity.

A casual wanderer can stumble upon a burlesque show in the ballroom, or a puppet show in the library, or a good old-fashioned performance of Richard III in the billiard room—even two actors purporting to be Edwin and John Wilkes in conversation. The play explores what led John Wilkes to assassinate Abraham Lincoln; a select few attendees also get a personal tour of Edwin’s haunted bedroom.

Brothers Booth is the first immersive play ever mounted at the Players, which Booth himself founded in 1888. And besides being the kind of interactive experience that is currently in vogue throughout New York City and nationwide (most notably in the long-running Macbeth-themed installation Sleep No More), it is also an attempt by an institution usually considered a luxury item—geared toward an older, wealthier clientele—to reinvent itself in its 125th year for a younger, hipper audience.

Von Buhler is no stranger to immersive theatre. The first installment in her Speakeasy Dollhouse series, The Bloody Beginning, has been running at the Back Room bar on the Lower East Side since 2012 (see “The Walls Come Tumbling Down,” July/Aug. ’13). And she found the thought of mounting an immersive play about the Booth siblings in a historical landmark too delicious an opportunity to pass up.

“I love architecture,” von Buhler says simply, as she reclines on the couch in the Players Club’s wood-paneled Card Room one rainy March afternoon. “I love history, and I love the fact that this was Edwin Booth’s home, and that he made it into a club for actors. And then there’s the fact that his brother was also an actor—I wanted to get at the reasons why this successful actor became an assassin, and how it affected the family.”

“Take in the artwork, the photographs, the statues and busts, and all—you are in history,” says a character in Brothers Booth. Any habitué of the Players Club would agree; visitors are regularly regaled with anecdotes from the distant past. “Some of the old-timers have the best stories,” says Michael Barra, a Players member since 2005; he sits on the club’s events committee. Barra’s company Stageworks Media is the producer of the Speakeasy Dollhouse series, and he hopes to expand the franchise to historical sites in London and New Orleans, among other places.

“Frank Sinatra [who was a Players member] had a private suite upstairs, and he would bring women up in the elevator,” as Barra tells it.

The Players Club is one of the oldest clubs of its kind in the country, created by Booth as a site for actors to interact with contemporary luminaries. As Booth wrote in a letter in 1885, “We do not mingle enough with minds that influence the world. We should measure ourselves through personal contact with outsiders. I do not want my club to be the gathering place of freaks who come to look upon another sort of freak. I want my club to be a place where actors are away from the glamor of the theatre.”

Booth purchased the house on 16 Gramercy Park in 1888, making the site his home. He died there in 1893. Lining the walls of the club are portraits of past and present members, a veritable who’s-who of celebrities and politicians, from Morgan Freeman and Edward Albee in the present to Grover Cleveland and Mark Twain. The latter was one of the original incorporators of the club, and during Brothers Booth, audience members can sit and play cards on a table that belonged to Twain.

Booth is everywhere, and not just because the site was his house—the costumes he wore and the props he carried are on display; his death mask hangs on the third floor; a full-length portrait of him painted by John Singer Sargent hangs above the fireplace on the ground floor. It is said that Booth earned $50,000 for four weeks touring, the equivalent of $2 million today.

A side note: Booth was also not a fan of theatre critics and would not allow them membership. “I will have made enemies of all the theatrical critics, since none will be admitted and no dramatic papers permitted on our tables,” he wrote in a letter in 1889 to his daughter Edwina. “So you must expect to see your daddy much abused hereafter.”

Booth came from a family of performers, and according to von Buhler, a sense of competition was instilled in the brothers from an early age. She posits in Brothers Booth that the desire to be the more famous Booth may have been one of the factors that incited John Wilkes to assassinate Lincoln. “If John Wilkes

wanted to outshine his brother, he may have done the right thing, because everyone remembers him now—which is pretty sad, because Edwin was the talented star!”