Freddy Arsenault is living the dream. He’s appeared on Broadway; his nonprofit credits include shows at the San Diego’s Old Globe, Virginia’s American Shakespeare Center and Manhattan Theatre Club. But he is also $165,000 in debt, a holdover from having to borrow to attend the graduate acting program at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. Over iced tea in midtown Manhattan in April, Arsenault recalls receiving his first bill from Citibank, his private loan lender, shortly after graduation. “I owed about $1,200 that month. I panicked. I went into a cold sweat. I started thinking, ‘How am I going to maintain a career like this?’”

Considering that he only makes $815 a week performing at Manhattan Theatre Club (which amounts to $450 after union and agent dues), the obvious answer would be: Get a day job. So when he’s not onstage, Arsenault is a real estate agent. His student loan—which, unlike any other type of loan, such as a mortgage or credit card debt, cannot be discharged in bankruptcy—currently costs him $700 a month.

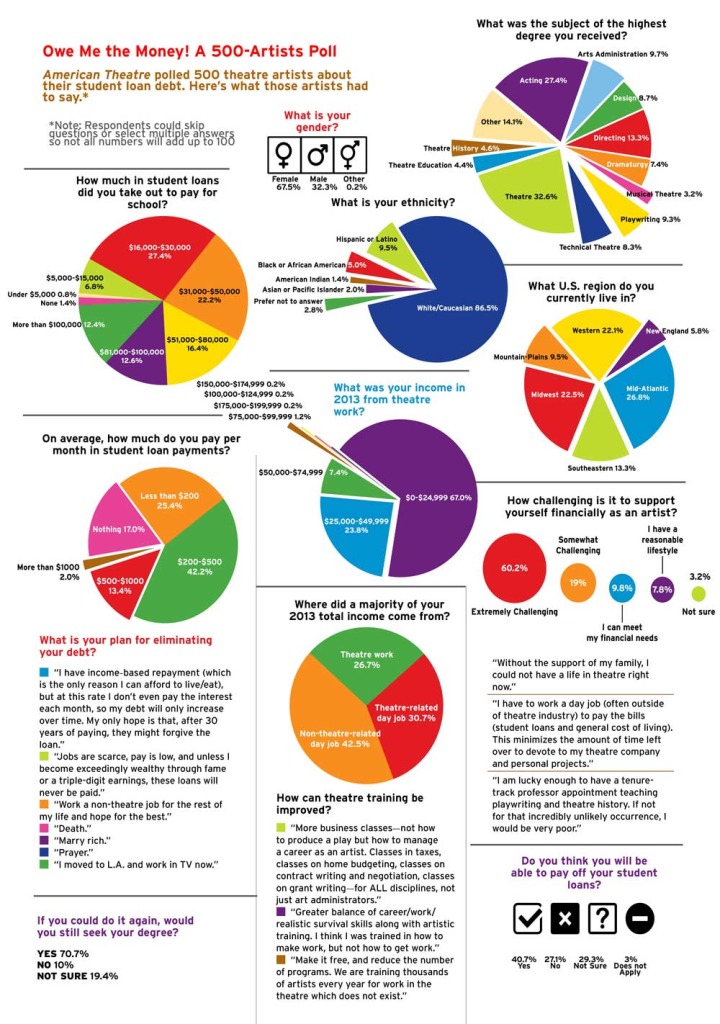

Arsenault is not alone. The national student-loan debt is estimated at $1.2 trillion and climbing. The average student debt load in 2012, according to the Institute for College Access & Success’s Project on Student Debt, was $29,400 for a bachelor’s degree. A separate study released by the New America Foundation tallied the median debt load in 2012 for those with both an undergraduate and graduate degree (for an M.A.): $58,539.

That’s the rub when it comes to higher education. A bachelor’s degree is a necessity for a career, and an M.A. or MFA is highly recommended as a way to quickly advance in a highly competitive field. According to a 2013 study from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Work Force, unemployment numbers for theatre arts majors stood at 6.4 percent, and 5.9 percent for those holding a graduate arts degree. (Compare that with those who major in education, whose unemployment rates run 5.7 percent at the undergraduate level, and 2 percent at the graduate level.)

Students graduating from theatre programs, armed with a diploma and a big bill, are facing an unstable, highly saturated job market. It’s an understatement to say that no one gets a theatre degree for practical reasons. “You have to want it beyond rational thinking,” says David Warshofsky, an assistant professor at the USC School of Dramatic Arts in California. “It’s not rational. It may be borderline irresponsible.”

“Don’t panic!” That’s one of the first pieces of advice Arsenault gives to outgoing students who are facing a lender bill. In order to combat the lack of counseling given to graduates about their loans—and to feel less alone in his debt struggles—Arsenault and two other Tisch acting graduates formed the Artists Financial Support Group in 2010.

The emphasis at AFSG is on being as proactive about debt as most artists are about auditioning or producing work. AFSG has held workshops at NYU, Yale School of Drama and the Actors Fund, among other places. The organization offers advice on what many would consider financial basics, e.g., budgeting on an erratic income, adjusting loan-repayment plans and (for incoming students) what to consider when choosing universities. “They don’t know how interest works on the loan, they don’t know what the payment plans are. They haven’t thought about the future,” says Arsenault. And for those who’ve left school, there are stacks of unopened envelopes. That’s the first rule, Arsenault emphasizes: Open the envelopes.

“If you ignore the minimum payment on your credit card or your utility bill, that’s when you get into trouble, and your credit is affected—which affects multiple areas in your life,” says Elaine Grogan Luttrull, a certified CPA who specializes in consulting for arts organizations. She’s given financial planning workshops at the Lark Play Development Center and PoNY (Playwrights of New York). “The best strategy is to not ignore [the debt]. It’s tackling it—and that may mean re-tackling the loans, deferment or some other active steps to make sure it’s under control.”

Some of AFSG’s advice is echoed in recommendations by Luttrull, including paying down the loan with the highest interest rate first (starting with credit card debt); putting some money away toward investments and retirement; and not being afraid to negotiate. “Our biggest piece of advice is: You only ever get what you ask for,” says Arsenault. To that end, they tell incoming students to ask for more scholarships and grants (“As soon as you sit down at that table, and they’re like, ‘We want you,’ you are at a negotiating table.”), and for graduates to negotiate a lower interest rate with their lenders.

“Your lender wants you to pay your debt—they’re not the enemy, but rather someone on your team that will help you figure out a plan that works,” says Luttrull. “Reduced interest rates, lower monthly payments, all those things are reasonable parameters that could be on the table.” Beyond that, be “forthright and upfront about what your ability to pay is.”

At the same time, there is no magical formula to make the debt completely disappear, especially not on an artist’s salary. “I don’t counsel people to try to get out of their debt. It’s a legally binding contract and you are responsible for full repayment,” says Hannah Kohl, who also leads free workshops on loan payment plans and consolidation. She’s led sessions at NYU and the Dramatists Guild.

Kohl finished NYU’s musical-theatre writing graduate program in 2009 with $140,000 in student loans. “[The program] did not offer any advice on what to do about our loans. It was made clear that very few of us would be able to pay back our loans with what we made from working in musical theatre,” she recalls in an e-mail message.

Though Kohl’s résumé includes working as script supervisor on Rocky, bothon Broadway and in Germany, and although she is working in theatre full-time, she has struggled with repayment. Through IBR, or income-based repayment (about which more info can be found at ibrinfo.org), she’s been given a breather: Her monthly payment is currently $0. Time is also a factor: Any payments made on an income-based, income-contingent or pay-as-you-earn repayment plan on federal loans will be forgiven after 20 to 25 years (depending on the plan).

“Since many recent graduates qualify for payments of $0 to $70 per month, I recommend that, when they can, they pay as much as they can each month to combat the interest. When they have a low month or two, they can drop down to the minimum payment,” Kohl explains. “You have to develop a long-term game and think of your future self. In 20 years, when your loans are forgiven, your future self will have to pay taxes on that amount. If you suddenly add $160K to your income, that’s going to be a pretty awful tax year.”

Most artists making IBR payments on student loans will find that their payments barely cover the interest without touching the principal, meaning that the total amount they owe is steadily increasing every month. For those artists, ASFG advises setting a deadline: Take the first five years out of school to “nurture your career”; sticking with low-paying jobs means you may be able to pay “something like $50 a month” toward a loan.

“But there has to be a line in the sand,” Arsenault concedes. “You have to have the discipline to say, ‘Okay, I’ve gone far enough. I’ve taken out this debt, and nothing has really been happening. I’m going to take on another job.’”

Between 2003 and 2012, student loan debt has risen 275 percent, from $241 billion to $904 billion, to a current level of $1.2 trillion. The rise in borrowing has increased alongside the rise in college tuition, which has far outpaced the rate of inflation and household incomes. Graduating students are left with very few options besides making their monthly payments and finding work that will cover that cost. “We’re just at the point of playing damage control,” says Arsenault.

Individual drama departments have taken steps to help incoming students alleviate their debt burden by offering more scholarships. At Yale School of Drama, the average financial aid recipient receives aid that covers 84 percent of tuition and living expenses over three years (2014–15 tuition is $27,250, and total costs range from $43,560 to $45,560).

“I would say that 10 percent of our admitted students have applied to our school because it was the only school that they can see themselves affording to train at,” reasons James Bundy, dean of the drama school and artistic director at Yale Repertory Theatre. “If we weren’t pursuing this policy, we would be effectively barring a meaningful pathway to entry to people who deserve it.” The student support comes from a general appropriations budget and Yale’s endowment, and Bundy believes that more schools can make fundraising for their students a priority.

If the cost of education is a barrier to entry, then why not lower that cost? Such a suggestion “shows a kind of vague understanding of how these things work,” says Laurence Maslon, the associate chair of NYU’s graduate acting program. “We can’t change the cost of the program—you’d have a less aggressive program.” He goes on to point out, “We lose over a million dollars a year for the university. We’re not taking expensive vacations to Cancun on our students’ nickel. Our money doesn’t go into capital improvements—our money goes into student scholarships.” NYU’s Tisch graduate acting department offers half scholarships to the students it accepts, but no living stipend; NYU’s estimates the cost of living in New York City at $20,000 annually.

Dr. Scott Walters, professor of drama at University of North Carolina–Asheville, a public liberal arts school, says that public university tuition has risen because of funding cuts from state legislatures, while private universities “have to be competitive, so the cost has risen. But I think those universities sell prestige, and if your tuition is rising because you sell prestige, that’s reprehensible. For what they’re doing to public universities, the legislatures should be shot.”

USC’s Warshofsky also acknowledges the bleak financial reality his students will most likely be facing, and that it will be “impossible to pay back these student loans” on an actor’s income. As an educator, knowing how much it costs for his students to attend USC and how little they will make in the field is “a burden on my conscience,” he says. “I guess if people stopped going to college, then tuition would eventually go down.”

It might seem more reasonable for medical and business graduates to amass up to six figures’ worth of debt, considering the average salaries in those occupations. But in a report from the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project (SNAAP, part of Indiana University’s Center for Postsecondary Research)—which surveyed 65,837 arts alumni across the country in 2011 and 2012 (nine percent of whom had received a theatre degree and who graduated as far back as before 1982)—the median income for those who worked in the theatre was $35,000.

“Artist compensation is a huge problem for the nonprofit theatre,” Bundy says flatly. “And there’s a lot of evidence that theatres are over-invested in fixed assets like buildings, and in fixed costs like administrative staff, and under-invested in compensating artists.” He also believes that the student loan issue is not one that can be solved with higher wages: “It will be fixed by reducing the debt from the get-go.”

It is an unwritten truth of the field that not all graduates will have a full-time career in the arts. When SNAAP surveyed 7,093 theatre graduates between 2011 and 2013, 10 percent of respondents said they left the field because of debt; 26.9 percent left because of higher pay in other fields. And, out of 6,882 responses, 17 percent reported that debt had a major impact on their career or educational decisions. No debt was reported by 42.7 percent of respondents (which accords with larger trends nationwide). At the same time, 75 percent of alumni reported that they would still attend their institutions if given a second chance. So it’s not the quality of theatre training that is feeding this student debt problem, it’s the cost.

“I don’t ever recommend taking on massive debt,” says Kohl. “I recommend finding a way to save the money beforehand, or to find scholarships or alternate ways of educating yourself.”

Those alternative paths may just be to do theatre without an MFA. Walters frequently blogs in the Clyde Fitch Report about the dubious value of the theatre MFA, and he is an advocate of bypassing graduate school and the New York City experience. He advises students to self-produce and to start their careers in the regions. “Instead of going to grad school for three years, do theatre for three years,” he counsels. And undergrad programs should be making it clear that there are “many, many different routes—they should be giving students the skills necessary to succeed in different contexts. We should require MFA programs to provide real numbers about how much it will cost, how much they will need to repay, and how much they are likely to make afterwards. Too many young artists don’t know these facts.”

In early May, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) introduced in Congress the Bank on Students Emergency Loan Refinancing Act, which would allow graduates to refinance their loans at the lower rate currently offered to new borrowers (3.86 percent). AFSG made its approval known.

Part of Arsenault’s long-range advocacy plan for AFSG is to assemble a political lobbying group that will push for lower interest rates, more lenient payback plans, and more education and arts subsidies, including bringing back subsidized Stafford loans for grad students (on which government pays the interest while a student is in school; these subsidies were discontinued for graduate students in 2012).

For now, Arsenault doesn’t see himself quitting theatre. The plan is to continue getting work, making money and “chipping away” at his loans. And how much does he have left, after paying $800 a month since 2008? “$165,000,” he says. “I still owe the same amount as when I graduated.” The reason for that is interest—though the principal on his private loans is going down, the amount he is paying toward his federal loans is only covering the interest, which means the total debt amount on those is ballooning.

Despite his debt, Arsenault is hopeful. After all, if he continues making on-time, consistent payments on his federal loans, they’ll be forgiven in 25 years. And if not? “There’s a book out listing 24 killer ideas for how to pay off your student debt. You want to know one of the ways? Sell a testicle,” he says with a wry laugh, before joking, “I’ll be a eunuch for my student debt.”