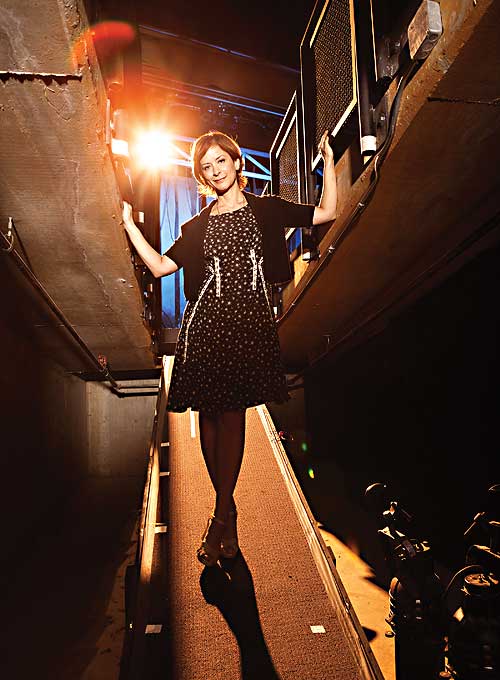

It’s not an overstatement to stay that Evanston, Ill., native Anna Shapiro grew up at Steppenwolf Theatre Company. Her mother began taking her to shows at the legendary Chicago repertory theatre when she was 12, and many of those experiences still burn vividly in her mind.

“I have a terrible memory—I just forgot my older brother’s birthday—but I remember those plays like it was yesterday,” Shapiro says. “I saw the original production of Balm in Gilead, directed by John Malkovich. I saw Orphans, You Can’t Take It with You, and—oh, my God!—True West, with Malkovich, Jeff Perry and Laurie Metcalf!”

That’s the same Laurie Metcalf that Shapiro herself, now 46, directed this past fall in Bruce Norris’s Domesticated at New York City’s Lincoln Center Theater. And the same Jeff Perry she directed six years ago in the Tony-winning production of Tracy Letts’s August: Osage County. So how did Steppenwolf’s most enthusiastic teenage fan become one of that company’s—and the American theatre’s—most acclaimed and in-demand directors?

A first step in the professionalization process, Shapiro figures, came when she was 14, and took an acting class taught by Steppenwolf company members Tom Irwin and Rondi Reed. But her first real break came some years later while she was attending Columbia College in Chicago. She directed a production of Pinter’s The Homecoming for her teacher and mentor Sheldon Patinkin. He knew that Jeff Perry was going to be directing a production of the same play at Steppenwolf, and recommended Shapiro to be Perry’s assistant.

A few years later, when Steppenwolf was undergoing a leadership change, Perry called to invite Shapiro back to Chicago from New Haven, Conn. (where she was attending graduate school at Yale), to meet with him and Gary Sinise about becoming a full-fledged part of the company. “It was impossible to pass up,” she confesses. “It was the first time I had been flown anywhere, and they put me up in a hotel. I thought I’d better rise to the occasion. I really wanted to work on new plays, and there was no real structure at Steppenwolf for developing new plays. They felt they needed to set up a commissioning system. You can’t be an organization that has great actors only and survive.”

Martha Lavey had just come to Steppenwolf as artistic director and she harbored a similar vision about the importance of new work—and Shapiro, she decided in short order, was just the asset the new initiative required. “What is so special about Anna is her acute psychological insight,” Lavey offers, now that the two women have several years of collaboration under their belts. “It helps that she’s funny and really smart and that the room is really alive when she’s steering the ship.”

Shapiro remembers those early days a little differently. “I was ambitious and probably really annoying,” she says with a self-deprecating grin. “But we cobbled together a new-play development program. I didn’t direct for a couple of seasons, which was probably smart, but it was hard for me.

“We built this theatre literally in the garage at Steppenwolf,” Shapiro continues, as we talk in her neatly appointed office at Northwestern University, where she is currently head of the MFA directing program. “Mostly to shut me up, I think, they were like, ‘Okay we’ll give you a 12-by-12-foot space in a room at the bottom of the parking structure, and you can do a play in there.’”

In conversation, Shapiro possesses a disarming combination of Midwestern nice and gruff bluntness. It’s not hard to see how she can be persuasive, and she admits that Steppenwolf has indulged her on many occasions.

One of those times, surprisingly, was when she lobbied for the company to mount August: Osage County. The award-gobbling Broadway hit seems like a no-brainer in hindsight, but there were substantial obstacles for the company to overcome, not the least of which was cost. “We couldn’t afford to produce that play. There were a lot of actors—and that set! It was incredibly risky.

“Martha and our executive director David Hawkanson were real advocates for us. They went to the board and said, ‘We need more money. We have no idea if we’ll make it back, but this play is a true example of a Steppenwolf ensemble piece.’ It was written by an ensemble member, directed by an ensemble member, with parts written for the ensemble—it was what we had been arching towards that whole tenure.”

“There’s nobody who’s dramaturgically stronger than Anna,” asserts Letts, who has known Shapiro since the late ’80s, when she directed him in a small production of Glengarry Glen Ross. “When you’ve first written a new play,” Letts continues, “it’s really helpful to have a director to help you understand what you’ve done. Some of it, for me, is a subconscious process. I always have a clear idea of what it is I’m trying to do, but a good director will say, ‘I get what you think you’re doing, but here’s what you’ve done.’”

Letts and Shapiro became immediate friends, but Shapiro had some strong words about his first play. “When I wrote Killer Joe, I gave it to her—and she hated it. She didn’t think there was anything there,” he remembers. “We’ve laughed about that since.”

As for August, during rehearsals the company had an ongoing bet about whether they’d lose more spectators between the first and second acts, or between the second and third. The play’s ending was changed “almost nightly,” Shapiro recalls. “It started to move into solely emotional territory without a strong plot—the impact of that emotional terrain is not big enough if it’s just hanging from nothing. You want emotional content, but you want it to hit hard—you don’t want it to be thrown softly, and plot throws that ball. We had a plot problem. And it came down to blocking: What does it mean if the character Violet walks toward her daughter Barb? What does it mean if Barb retreats at this moment? You don’t see a lot of plays where all the characters have the same value.”

When August moved to Broadway, Letts and Shapiro were as surprised as anyone when audiences flooded into the Imperial Theatre—and stayed. “Tracy and I thought we’d be there for a few weeks, and then they’d spank our bottoms and we’d go home,” Shapiro jokes. “Then previews started, and we’d be like Gene Wilder and Zero Mostel in the back of the theatre, and we’d look at each other and wonder, ‘Who is coming to this play?’”

When Shapiro attended the 2008 Tony Awards ceremony, it was the first time she ever set foot in Radio City Music Hall, and the experience was overwhelming—so much so that she almost didn’t stay. “I turned to my husband” (actor Ian Barford, who played Little Charles in Osage County) “and said, ‘I can’t do this!’ He grabbed my hand and told me to pull my head out of my ass. He said I had to think about it as a strange planet I was visiting.”

Shapiro found herself back on that planet a few years later, in 2011, when she directed the world premiere of Stephen Adly Guirgis’s The Motherfucker with the Hat. “It was supposed to be at the Public Theater, and I’ve wanted to work there my whole life. I cried when they told me it was going to Broadway. I’m not kidding,” Shapiro confesses.

Unlike August, Motherfucker had never been previously mounted, and Guirgis was still rewriting well into previews. “It wasn’t good—Stephen was trying desperately to find the play. Like many writers, he finds it in fits and starts. There would be many days without any changes and then suddenly 25 new pages, which is hard enough for people who have been in plays their whole lives. But Chris Rock had never been in a play before, and, bless his heart, he was busting his ass just to remember what came next.”

Despite having a love for his stand-up, Shapiro was initially skeptical about Rock for the play’s lead; producer Scott Rudin had to convince her to let him audition. “He came in and read the whole play. He sat next to me, which I thought was unbelievably sweet and unknowing—I’m not even sure he knew I was the director. He had written some notes to himself on his script—I won’t tell you what—but it cued me in to what a wonderful human being he was.”

Still, even with theatre veterans Bobby Cannavale and Yul Vásquez on hand to support Rock, Motherfucker wasn’t coming together. “We were tanking, despite what anyone says now—they thought we weren’t going to open, man,” Shapiro laments. “I had a stomachache for like six weeks. I was so worried that I was failing, and I didn’t know how to fail. I remember going for a walk with my husband Ian when I could barely talk. He said to me, ‘You know, most philosophers talk about ambition as being a phase of life,’ and I burst into tears.”

Motherfucker did ultimately come together to become a critical and commercial success—which sped the momentum gathering around Shapiro as a director who can make both thought-provoking work and money at the box office. But it was only the beginning of the questions she asks herself about her place in the theatre. The next phase after ambition, she figures, is service, which is how she sees her role at Northwestern.

Directing for Shapiro is not a mystical profession, and she doesn’t believe it’s hard to teach to others. “You have to understand that your job is a not-mysterious combination of interpretation and inspiration. You have to understand yourself as the person who has called the party together, regardless of how you’ve gotten in the room, because a lot of times it sure doesn’t feel that way. Early in your career you’re just so fucking desperate to get into the room—you feel so grateful to be there. But that kind of feeling goes away after about 48 hours, when you realize you have no idea what you’re doing. First you’re happy, and then you’re lost,” she posits bluntly.

Successful directing eventually comes down to story, she says—not just what the story is and who’s telling it, but, “What is the director’s personal investment and connection to the story?” She emphasizes this with her students.

Teaching, in fact, acts as a grounding force in her life, but Shapiro has no illusions about how some of her students might view her more commercial endeavors. “They think of me as ‘the man.’ They don’t necessarily want to follow my track,” she explains. “They’re kind enough not to argue back, but how is presenting James Franco in Of Mice and Men on Broadway a conversation with the culture? It’s a legitimate question.” (Shapiro’s theatre-devoted parents were Marxist in their politics, so that’s a question the director tends to ask herself often.)

The high-profile Steinbeck-on-Broadway project—previews are slated to begin March 19 at the Longacre—is likely to hike Shapiro’s profile up several notches. And she has some serious thoughts about the play’s political implications. “I think it’s a beautiful piece of work—and it’s about things that are important to me right now,” she allows. “It’s a conversation about the American dream and what men are promised—certainly straight white men—and how that lie crushes them later in life. It’s about how dangerous it is to let your dream live outside your body; about what friendship is, and the cruelty of a world where utility is all that matters. I don’t think there’s any time in the history of our country where those themes would be irrelevant.”

Shapiro has wanted to direct Of Mice and Men for years, she says, and, indeed, pictures of the set of a Broadway-bound production that never came to be are tacked onto a bulletin board above her desk as a reminder “not to get attached to things, because they might not happen.” When she heard that funding for a new production had been secured, the project was hard to pass up. James Franco was attached, and this time it was the director who would be auditioning for the star—which was fine with Shapiro: “Commercial theatre is like the NBA. I’m not LeBron James. If I’m lucky, I’m the guy who coaches LeBron James.”

Shapiro and Franco ended up hitting it off and talking for hours about Steinbeck and the play—to the extent that now she can’t remember what he said and what she said. Everything you might have heard about Franco’s eccentricities is true, she acknowledges, but it doesn’t bother her. “I love him. He’s a really enigmatic dude, in a way I don’t find problematic. He gets the play and he gets Steinbeck. He’s not uncomplicated, but that doesn’t bother me. I don’t find uncomplicated people that interesting.”

She did warn Franco, whose stage experience is limited, about the rigors of theatre. “I told him there’s no one who stands in for you when the lights are being set in tech. You don’t shoot all your scenes and then get to leave. It’s a physical and spiritual endeavor.”

It’s an endeavor, furthermore, that’s bringing the actors to Chicago to rehearse during February in the dead of an especially dire winter. Actor Jim Norton has been particularly eager to work with Shapiro since meeting her at a Tony party back in ’08. “Not only is she a brilliant director but a fully rounded human being who strives to balance her home life with her career,” Norton explains. “She knows that family trumps all.” Indeed, Shapiro pushed for the Chicago rehearsals in order to stay closer to her family, which includes a young son and daughter. After Of Mice and Men (and one additional Broadway project she’s keeping secret for now), the director won’t be staging a play in New York “until 2016 at the earliest,” she avows.

“The best room in my life for so long was the rehearsal room—that was the room I wanted to be in, and I would have done anything to be there, but now there are other rooms that have a lot more pull. To get me back in rehearsal, a project is going to have to have a lot of weird, personal, probably not explainable components.” Working with Franco clearly fills the “not explainable components” bill. Shapiro is also dying to do “a dark production of Noises Off” at Steppenwolf, but she figures it will never happen because artistic director Lavey thinks it’s a terrible idea.

In keeping with her developmental focus at Steppenwolf, Shapiro reads new plays whenever she can. While she doesn’t judge a script by its cover, she confesses she does by the way the pages look. If there are lots of single-line exchanges, she’s immediately skeptical. “The lines have to be great and not complete—fast exchanges won’t work. I love clever play, but I don’t want to direct them. I don’t think there’s anything to do. They end up being weirdly unsatisfying for the actors and the director.”

Shapiro’s frequent collaborator Bruce Norris (who has rarely been accused of being enchanting) is part of the Steppenwolf family, and the two artists have the kind of comfortable exchange that comes with familiarity. When Shapiro directed his Domesticated at Lincoln Center, one of the main draws was that, besides Metcalf, she had never worked with any of the actors before. “It’s nice to be with people who have only known me as an adult,” she quips.

Another draw was the pace of the play, which moves with a fluid and quickening pace as the life of a powerful man, played by Jeff Goldblum, unravels. “Plays,” Shapiro is convinced, “are about how they move. The first thing to figure out is what’s happening and what’s the conversation that the play is trying to have with the audience—that informs how a play is staged. It’s kind of onomatapoetic—there’s a repetitiveness and reductiveness to the way Domesticated was staged that is very much Bruce’s intention.”

Norris, never one to shy away from uncomfortable ideas, also worked with Shapiro on another memorable play, The Pain and the Itch, which involves the mystery of how a toddler has contracted an STD—but it’s also about how people hold tightly to entrenched beliefs and the miscommunication those beliefs can cause. “It has an engaging form and asks very difficult questions, and I think it’s more compassionate at times about those questions than some of his other plays can be. I’m a little softer than Bruce, so I appreciate it,” Shapiro elaborates.

The Pain and the Itch, like so many of the plays Shapiro has directed, debuted at the theatre where the art form imprinted itself on her as a child. The question of why she keeps coming back to the source seems to have an obvious answer—it’s like asking someone why they keep coming home. “Steppenwolf has always been the spine of what I do,” Shapiro insists, “and wherever I go and whatever I take on, I expect it always will be.”

New York-based arts writer Christopher Kompanek is a frequent contributor to this magazine.