Contrary to popular belief, people don’t always like new things. Sometimes people don’t even agree whether something really is new or not.

Take the question of “the new” to theatre artists, some of whom have been working in the profession for decades, and the response seems to be contradictory: Theatre is bursting with new technology, the likes of which we are still not clear on how to deploy effectively—and yet there is nothing new about theatre. We tell stories. We put actors on a stage, give them an environment, ensure they can be seen and heard when necessary, and tell the story the best we can.

Charles Otte, who heads the Integrated Media for Live Performance program at the University of Texas at Austin, concedes that the word “new” can be misleading. “Innovation is built on the work and research that precedes it, and I suppose if you wanted to be really reductive you could look at the ones and zeroes of digital communication as a kind of hammer stroke,” Otte writes via e-mail. “On and off. On and off. Open close, open close. But I think that reducing things to that level is a little ridiculous.”

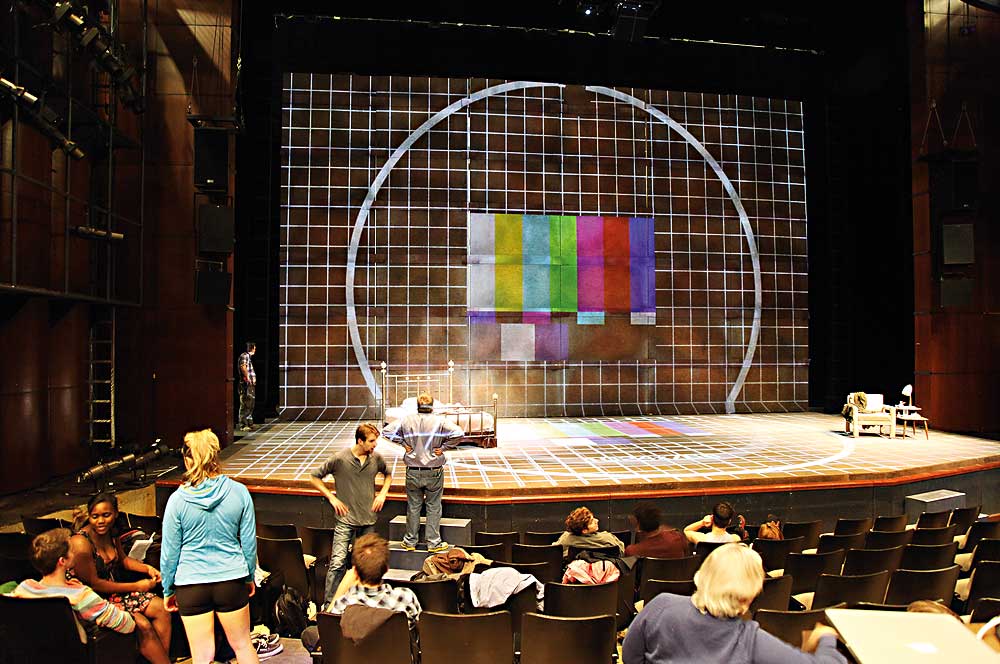

According to Otte, what’s new can be thought of in three parts: computers (“and by extension lighting, audio and show-control systems”), media and projection design (“changing not just scenery, but the ways in which we interpret scenery”), and the interactivity ushered in primarily by social media (“many companies are looking toward social media as an avenue to engage audiences”).

As the executive artistic director of 3-Legged Dog (3LD) in New York City, Kevin Cunningham leads one of the most technologically innovative organizations in American theatre. He believes that the recipe for what is new in the theatre can be found in a code Otte compares to a hammer stroke.

“The profound technological change in live performance has been the use of digital code as a sort of universal translator between different technical elements of a show,” Cunningham says. “Tools for the creation of digital content and the pervasiveness and ease of use of these tools have made the manipulation of image, sound and physical devices much easier and more affordable than before. And these capture and edit tools are available in native form on most digital devices, so younger artists—many literally born with a laptop in front of them—incorporate moving image and other media into their work as readily as they use it in their daily lives.”

There is a reason that both Otte and Cunningham put computer technology at the top of their list. It is pervasive, and contributes to each and every area of theatre that is considered new or emerging. “The actual means of execution are new, and require new training,” Otte says. “John Henry driving rail spikes in competition with a machine will always lose the race. Leaps in technology create new jobs and make others redundant.”

This churn can be positive—if theatrical technicians are prepared. John Huntington, professor of entertainment technology at New York City College of Technology (City Tech), tells the story of an old Broadway general manager reminiscing about crew size for Broadway shows. When asked if the crews today are bigger or smaller than they once were, he explained that the number of technicians required to mount a production decades ago was quite the same as today—the difference is what the technicians are doing. Instead of moving scenery by hand, they’re operating automated scenery, for instance. You need the same number of bodies, in other words, but the skills they require have changed dramatically. And the skills have become far more complex, too.

In 2002, Huntington wrote an article for USITT’S Theatre Design & Technology called “Rethinking Entertainment Technology Education.” He wrote things like “the language of live-performance storytelling is now evolving fastest outside the theatre world,” and “I don’t believe the college educational system has adequately responded to the needs of this new media-saturated, entertainment-driven world.” Huntington has been training entertainment technicians for a long time, and his observations are not those of an ill-informed doomsayer. “That article is more than 10 years old, but it’s still pretty accurate,” he told me recently.

If he is right—if his examination of all that was wrong with how we were training technicians more than 10 years ago could be published today with little alteration—then we might have something to worry about.

“John Huntington’s entertainment technology program at City Tech is turning out top-notch professional stage technicians,” 3LD’s Cunningham confirms. But that program is an exception, he points out, not the rule.

“The number of calls we receive routinely from universities trying to find a way to come into the 21st century and serve these kids hasn’t diminished,” he says. Across the country, programs addressing new and emerging areas of theatre technology are popping up—especially when it comes to video and projections [see sidebar]. But Cunningham is frustrated by the path they are taking. “It’s about time programs like these were put in place, but they miss the critical aspect of digital stage technology as it is developing,” he says. What’s missing, he claims, is integration and interdisciplinary training.

Otte, whose program at UT Austin is in its fourth year, agrees. “I think that Kevin is on to something,” he says. “Technicians, directors and designers in theatre need to understand how the theatre machine works in order to effectively create new and interesting work.”

Cunningham singles out Jared Mezzocchi and his burgeoning program in multimedia at the University of Maryland as one artist trying to broaden the focus of technical training. The UMD program is small, with just 20 students spread throughout the theatre, dance and performance studies departments rather than in their own MFA track. “A large number of my undergraduates have been designing projections both in school and outside of school,” Mezzocchi says.

But others, like Otte’s program at UT, are in tune with Cunningham’s hope for the well-integrated future of technical theatre. Otte’s program includes coursework in filmmaking, animation, video production, audio design, projection design, building mapping, editing, digital rendering and game design, as well as traditional design and technology courses. “In addition to theatre, the program emphasizes creative design for other venues including museums, theme parks, retail space, interactive displays, filmmaking and multimedia installations,” Otte enumerates.

“No one is coming at it from just one angle—you have filmmakers coming at it, you have photographers coming at it, you have high-end installation artists coming at it,” says Mezzocchi, who recently designed The Downtown Loop at 3LD. The program in multimedia design at UMD is still quite new, and he enjoys contributing to the future of the field. I ask him (as I did everyone I interviewed for this piece) where were the technicians learning to operate and program all of the multimedia technology currently being deployed. He admitted that it was a mixed bag. “They’re emerging a lot more regularly now that there are places teaching it,” he ventures. “In the past it was a lot harder to find programmers and operators.”

Lauren Joy is one of Mezzocchi’s students at UMD. “This is a field of discovery and innovation, and I want to be a part of it,” she says. “Jared is well aware of how high the demand is for people who are trained in not only programming, but also in being able to flesh out a solid design concept and hook up their own equipment.”

“Media design is still very much a custom field, and each show demands certain tools and skills,” Larry Shea of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh believes. Shea runs the video and media design program at CMU, a relatively new program, with just three graduate students. “While there are great professional systems that we train our students with, they really need to be systems designers as well as visual designers,” he says. “Now these kids can all do some sort of programming, so they make the tools they need—and since no one person can do it all, we focus on building creative teams and collaboration as the foundation of the process.”

With a growing emphasis on training a pool of practical designers—those with the skills to conceive, create and implement their multimedia designs—Huntington believes that what’s really missing are visionary directors.

“We can pretty much do anything on a stage these days, but I would argue that we are limited—especially in the theatre—only by our creative imaginations,” he says. “For the majority of theatre that I come across, the directors don’t seem to understand how to use modern technology to tell the story.” Huntington, who has degrees in theatre from Ithaca College and Yale and is the author of Show Networks and Control Systems and its precursor Control Systems for Live Entertainment, listed high-profile directors Robert Lepage and Alex Timbers as notable exceptions to this generalization (and admitted that there is probably work going on of which he is unaware).

More concretely, Huntington points to fundamental gaps in how we educate theatre technicians and designers, including a general failure to focus sooner on show control and networks—his field of expertise and another big part of modern theatrical technology. Training in this area—which includes coordinating and linking multiple entertainment control systems, such as lighting, sound and video—is still considered a high-level specialty, according to Huntington.

“I know of few undergraduate or graduate programs in the U.S. that require all technical students to take on this topic,” he says. “And I think this is very short-sighted. Every modern technical entertainment system—lighting, sound, video, scenic automation, etc.—is built on Ethernet networks these days.”

The emphasis of the coursework in the Video for Performance program at California Institute of the Arts in Valencia addresses exactly what Huntington is most concerned about: vision.

“While there is a strong need for highly specialized skills in terms of execution—and our program provides for those—the most successful and groundbreaking artists are able to think of the big picture, and figure out how to use the tools at their disposal to their greatest overall potential in service of ideas,” says Peter Flaherty, the head of CalArts’s program. “This requires an understanding not just of skills, but of cultural theory, emergent artistic forms and practices, an evolved collaborative ability—and, most important, the ability to conceive and create as a generative artist.” The VFP program was initiated two years ago as a response to what Flaherty calls a “strong student interest,” as well as the increasing presence of video in theatre and performing arts. “It became obvious that there was an educational gap,” he says.

Technology has not only changed the way things work onstage or what can be put there—it has also made the act of collaboration much easier and, perhaps more to the point, faster. “We have the same amount of time to get things done, but what we can accomplish in that time has improved dramatically,” Huntington says.

Cunningham considers this improvement, and the communication tools theatres and artists now regularly employ across the globe, to be critical to the success of a company like 3LD. “Even as a mid-sized not-for-profit, we are currently actively building projects and collaborating with companies in Asia, Europe and South America,” he says. “We routinely work across national boundaries now because the entire show can be represented in great detail inside a set of digital files. The entire design is originally created in a Vectorworks or CAD drawing that includes all the information a knowledgeable person would need to specify and build the entire show—set, lighting, sound, video, machines and devices.”

Cunningham goes on to note that the right multiplexing software can literally hold all of the actual cues in a complex multimedia show, and that can be e-mailed to the venue while a drive or DVD is shipped with the large files to be loaded on the house computers. “Just 10 years ago, this would have been impossible.”

“From a practical standpoint, the reasons we have seen such a rapid increase in new media in the arts in recent years include the affordability and availability of creative tools,” Flaherty elaborates, “and a greater general facility with those tools at a younger age.” This means that the tools are there to take advantage of, if—as Huntington would be quick to point out—the director’s vision calls for it. It is only natural that such a vision would include the interconnectivity of our digital age.

“We increasingly experience the world around us in our day-to-day lives through moving and interactive images,” says Flaherty. “I think it is not only familiar to our audiences as a platform for communication, but an essential aspect of modern life for artists to explore and unpack.”

PROGRAMS OF STUDY FOR VIDEO, PROJECTIONS AND MULTIMEDIA

Arizona State University Tempe, Ariz.

MFA in Theatre, Interdisciplinary Digital Media and Performance

theatrefilm.asu.edu/degrees/grad/mfa_theatre/digital_media.php

LDInstitute@ASU professional program in projection and content creation

http://livedesignonline.com/news/ldi-and-asu-announce-immersive-training-projection-and-content-creation

California Institute of the Arts Valencia, Calif.

MFA in Video for Performance

theater.calarts.edu/programs/design-and-production/video-performance

Carnegie Mellon University

Pittsburgh, Pa.

MFA in Video and Media Design

http://www.drama.cmu.edu/257/video-media-design-g

University of Maryland

College Park, Md.

School of Theatre, Dance and Performance Studies; multimedia design curriculum available to B.A. and MFA students

tdps.umd.edu

University of Texas at Austin

MFA in Design and/or Technology

www.utexas.edu/finearts/tad/graduate-programs/mfa-design-andor-technology/technology-curriculum

Yale University

New Haven, Conn.

MFA and Certificate in Design

drama.yale.edu/program/design

A writer and theatre artist, Mike Lawler spent many years as a technician in theatres across the United States. He has written widely on the theatre, including his book Careers in Technical Theatre. For more go to www.mikelawler.com.