For the past 50 years, Bread and Puppet Theater has made a name for itself by doing things many serious theatrical practitioners consider taboo. The company makes what its 79-year-old founder Peter Schumann calls “nonsense puppet shows” in a country that largely regards puppetry as a form of entertainment for children. They charge nothing (or very little) for admission to their shows. And they make highly politicized—and often overtly didactic—presentational theatre, centered almost exclusively on the experiences of the oppressed, the radicals, and the refugees of the world.

Consider this list of heroes and heroines from past Bread and Puppet shows: Joan of Arc; the 17th-century Italian fisherman Masaniello, who led a revolt against Hapsburg Spain; Adolfina Villanueva, an artist murdered by the police in Puerto Rico in 1980; Archbishop Óscar Romero of San Salvador, assassinated by right-wing death squads the same year; Brazilian rain-forest advocate Chico Mendes, who likewise died for his cause; and Mexican Revolution leader Emiliano Zapata, to name a few. Groups and populations organized around social and political causes have also been at the center of B&P works: Vietnamese women; M.O.V.E., the radical group against whom the Philadelphia police department waged war in 1985; and, most recently and most expansively, the world’s immigrant and refugee populations, in Schumann and company’s new spectacle Shatterer of Worlds Chapel with Naturalization Services for Applicants Requesting Citizenship in the Shattered World.

Work began on Shatterer of Worlds in 2012 on Bread and Puppet’s 20-acre, green-meadowed farm in Glover, Vt. Schumann wanted to focus his lens on the dehumanizing processes faced by countless uprooted individuals the world over. One of the chief texts used in the piece is Department of Homeland Security form I-212: “Application for Permission to Reapply for Admission into the United States After Deportation or Removal.” Of course, the roundabout title of the performance mirrors the circular language of the aforementioned form. So, too, does the anti-choreographic method Schumann employs in the creation of the piece.

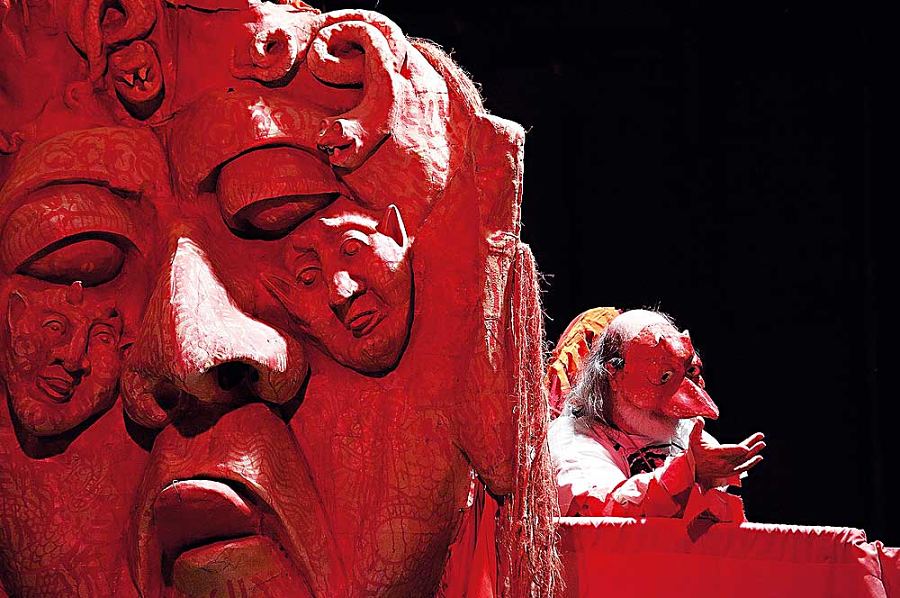

I am one of 50-odd performers invited to the farm to invent, rehearse and perform Shatterer of Worlds. Our first rehearsal begins with us milling about in a workspace that resembles an old barn, feeling the cool earth beneath our bare feet. The building has become a kind of papier-mâché cathedral, its walls completely encrusted with bas-reliefs depicting human suffering: bodies caught in various forms of fragility, faces frozen in agony, refugees marching in an eternal exodus, forever trapped between home and some mysterious destination. Both the square earthen stage, contained by walls on three sides, and the backstage area serve as performance spaces, opening up different planes for Schumann’s arresting tableaux. Above the upstage wall runs a platform, representing the heavens; above that is the well, a trap door through which various puppets may drop in and fly out.

Much of the action occurs in darkness, occasionally illuminated by a roving floodlight. Two structural elements frame our loosely improvised movement. First Schumann reads to us from J. Robert Oppenheimer’s anguished speech about the Hiroshima bombing, in which he quotes from the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the Shatterer of Worlds” (most of us probably know this quote with the slightly different translation “destroyer of worlds”). Then Rose Friedman, an ongoing B&P collaborator and co-founder of Boston-based Modern Times Theater, who is stationed at a small desk, rings a service bell: Ding! Dancers line up across the stage. Friedman reads random questions from form I-212: “What is your country of origin?” She is met with silence. “Do you have any tattoos?” Again, silence.

My role—which was given to me, surely, for my recently demonstrated mastery at hand-milling rye berries into flour—is to operate an old-fashioned wind machine, one example of technician Peter Hamburger’s brilliance in inventing instruments with found materials. I have been turning the pulley, connected to the heavy wheel, for nearly an hour. My arms burn; my back aches; yet I go on turning, waiting for Friedman’s bell to give me respite.

When at last the bell dings, I halt. The lamp on Friedman’s desk clicks to life. “Next,” she begins. “Do you have any customer service experience?” Silence.

“Those questions,” Schumann says as he stands before us in a post-rehearsal session, “reveal exactly what society expects of its citizens.” Though Schumann rarely discusses theory, he ventures a thought on dance: “Remember, we are not doing choreography. You must take initiative. Move, or don’t. A dance occurs when you walk from one place to another. That’s all we need.” A thoughtful silence. “Still,” he smiles, “there were some moments that were fantastic.”

In the weeks leading up to my arrival at the farm in Glover, I find myself in the West Village, New York City. I walk daily past the Judson Memorial Church near Washington Square Park. These are the streets on which Peter Schumann founded Bread and Puppet Theater in 1963. Though they struggled for collaborators and audiences in those early years, Schumann and his wife Elka persevered.

One of their early supporters, Judith Malina of the Living Theatre, says, “I knew Peter was a true artist when we first met. He was both revolutionary and lovable.” She offered Schumann a performance workspace in the Living’s former home on West 14th Street. But when the Licensing Bureau of New York City began waging war against avant-garde theatres (especially those who presented revolutionary content), Malina and her partner Julian Beck were jailed for contempt of court while being tried for ostensible tax violations.

Schumann, in the meantime, had begun performing in his loft at 148 Delancey Street. Again the Licensing Bureau came calling, this time with a summons accusing Schumann of “holding a puppet demonstration in his loft, and specifying amount of contribution.” Though these legal battles were a hassle, they had the effect of sending B&P out onto the streets, where the company eventually found the collaborators and audiences it sought, and flourished.

The Vietnam War was underway, and, as it gained momentum, more and more people poured into the streets of New York and other American cities to protest. Elka stresses the important role the war played in B&P’s development: “The people were hungry to express their feelings about the Vietnam War—they wanted to participate, and Peter wanted to do big shows. Those things fed each other.”

Schumann was no mere opportunist. He had specific reasons for going into the streets. In an interview with Stefan Brecht for the 1988 book The Bread and Puppet Theatre: Volume One, Schumann talked about the difference between the effects of media reportage and performance: “The news is designed to be benign, comforting. It creates images for easy consumption. The street parade is different, however, in that it makes the harsh facts ‘real’—physical. It’s upsetting. It’s in your face. It cannot be soothed simply by changing the channel.”

Of the pieces performed at the time, 1968’s Fire garnered the most attention. Fire was inspired by two instances of protest in the U.S.: Norman Morrison, a Quaker, set himself aflame beneath the office window of former U.S. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara; and Roger LaPorte, a devout Catholic who took up the lotus position on U.N. Plaza, also self-immolated before a crowd of spectators.

“Fire was so strong, so immediate,” recalls Christian Dupavillon, curator for the World Theatre Festival at Nancy. He invited Schumann to Europe but, Dupavillon recalls with a shrug and a laugh, “Peter declined. He preferred New York.” The curator persisted, and eventually won Schumann over with the promise of a meeting with Helene Weigel, the widow and collaborator of Bertolt Brecht. So, in the summer of 1968, amid student strikes and labor revolts, Bread and Puppet performed Fire and A Man Says Goodbye to His Mother in France. Dupavillon says with subtle pride that “the performances were sold out perpetually.”

The Nancy engagement was Bread and Puppet’s first financial success—and the one that allowed the company to focus its energies fully upon making theatre. When asked why he remains faithful to Schumann, Dupavillon says: “Peter doesn’t change with success. After 50 years, he’s still making the same kind of work. It’s still meaningful, and done in the same spirit.”

Bread and Puppet’s anniversary summer brings more than our 50-person cast of Shatterer of Worlds to the farm—there are hundreds of collaborators, present and past, on hand from around the world. Three other shows are on in simultaneous development: new works called The Total This and That Deathlife Circus in Two Parts: Part 1–This, and Part Two–That, and a remounting of Birdcatcher in Hell, B&P’s 1971 interpretation of a Kyogen, the comic interlude of an ancient Noh play.

The place is buzzing with life and activity. One sunny day, after chopping wood, I walk distractedly past Brooke Stapleton, a B&P volunteer for 10 years, and Margo Lee Sherman, who has performed with the company since the late ’60s. They sit on the ground, near Schumann’s giant Quebec-style clay oven, with pails and pans full of mud. Stapleton becomes good-naturedly indignant at being ignored: “You’re going to walk past two old ladies playing with mud, and you aren’t even slightly interested?”

The scene before me suddenly comes into focus: The two women are merrily making mud-pies and cakes embellished with choke-cherries. “I am an expert mud-baker!” Stapleton exclaims with glee.

Sherman asks me: “Have you ever thought of Peter as a boy? A little boy like other little boys?”

I know the story. Schumann was a boy of only 10 when he and his family fled Silesia—a region then within Germany’s perpetually shifting borders—effectively joining millions of other World World II refugees. They took with them little else besides black rye bread. It was from his mother that Schumann learned to bake, and the bread that he makes in the onsite clay oven is given to the audience after every performance. When we—the performers and the audience—eat bread together, we partake in a ritual that hearkens back to Schumann’s formative years, when he first performed puppet shows for his fellow refugees.

Sherman continues, a glint of light in her icy blue eyes: “We toured London in the ’60s. There was a museum there with Egyptian bread—it was hundreds of years old. Guess whose bread it resembled?”

Our days on the farm are rich with such interaction. Friends and family members reunite, strangers forge new connections with one another, stories of respective homes and journeys fill the air. Whether you’re committed to helping with farm chores or making contributions to the development of the various shows-in-progress, there is always something rewarding to do. Clare Dolan joined the company in 1990 because, as she puts it, “Bread and Puppet makes use of my skills and interests—namely, making things with my hands, performing hard physical work and constantly engaging with world events.” Today Dolan is on the board of directors and also does special projects, including teaching workshops. One recent workshop, in Ramallah, Palestine, was transformative for her. “We taught theatre and parade-making to a group of visual artists. They lived in occupied territory and they had to pass through checkpoints on their way to and from class. Students wouldn’t show up, and we’d learn that they’d been detained. No one there had ever been to the sea, though they could see it from afar.”

A common thread that connects those who get involved with Bread and Puppet is an interest in activism, the impulse to work for transformative change (or, in some cases, to preserve things precisely the way they are), whatever their specific political orientation. Rosa Márquez, a retired professor and theatremaker from Puerto Rico who has worked extensively with B&P throughout Latin America, calls Schumann “the ultimate Marxist. He’s created an alternative economy right here in Vermont. One of Peter’s greatest achievements is that he thrives here while completely swimming against the current.”

Two years ago, I heard Schumann say to a group of collaborators that he wished “refugeedom” for us all. At the time, many were perplexed by such a wish. But it was as a refugee, Schumann reasoned, that he had learned about such practices as baking bread, farming potatoes and picking berries, building community and puppet shows—all things that he considers essentially good and that he continues to practice to this day.

I find a private moment with Schumann to ask him about Shatterer and its progress. He becomes deeply reflective; his eyes flash. “The process has been amazing. Working with people from such diverse backgrounds. The piece is loaded with people’s histories. It shows that we aren’t spoiled by super-duper civilization. We can hook back into communal exercises. No more being pampered for society’s good. We can change.”

Flash forward: Schumann begins the final Shatterer rehearsal by begging us for anarchy. “It’s so beautiful when you take initiative—when you choose to do something, and then do it.”

Márquez, sharing her thoughts, describes Shatterer as “structured improvisation. One gets sensations rather than certainties.” When performing such work, of course, the mark of success is ever elusive.

Still, Schumann knows what the piece needs to become: “All the cues we’ve learned—forget them,” he instructs us. “They’re killing your inventiveness.” We have our final performance in a mere three hours, and his directive makes my hair stand on end. “The dances have become boring—I want initiative again.” With the rug pulled from beneath my feet, I suddenly feel like I can fly. “We need to bring back the architecture. It’s a chapel, but we have turned it into a basket of wriggling worms.”

This last phrase draws from me a spontaneous guffaw: I’m reminded how rarely the right words are used to describe a problem—and of something even scarcer: how few people find the courage to be so honest, so direct. Schumann goes on: “Don’t forget where this piece comes from: the twin atrocities of the German invasion, and the revenge attacks that followed, displacing nine million people. Such a migration is rare in history.”

A young woman in the cast wants to know: “Is that what we are? The refugees?” Schumann responds, “No. Don’t imagine that you’re suffering. You’re not.” “Where should I put my imagination, then?” “In the dirt. Hollywood teaches us to pretend suffering. We have abandoned that. We are making a vibrating sculpture, not an imitation.”

Schumann’s words are, like his theatre, clear, bold, cutting. He is all too aware that his theories and practices are the antitheses of what many of us have been taught. Still, he persists. His courage is infectious. “Shall we begin rehearsal?” he asks. One can feel the energy in the air, buzzing, pulsing, engulfing us as we take our places.

Flash forward again: It is a few moments before the final Shatterer performance, and I’m hiding behind a towering, 18-foot-tall Bystander puppet. To ground myself in the moment, I run my fingers across the surface of the puppet’s knee: the texture reminds me of baked mud. The smell of earth is in the air. The audience fills the space. Schumann shuts the heavy barn door.

Once the pre-show announcements are delivered, I walk out to light the candle that rests upon the audience’s side of the wind machine.

With the candle lighted, I lay my hands upon the pulley and begin to turn the wheel, slowly at first. The sound of faint, distant wind fills the space. Then I ramp up the pace, increasing the volume and tempo of the wind—faster and faster!—until the sound resembles a tempest. I maintain this crescendo for only a moment before gradually slowing the stream of air.

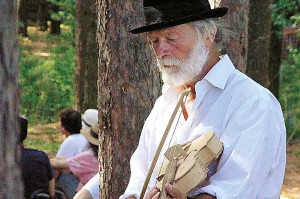

As the wind falls silent, Schumann, seated near center stage, begins scratching at his crude single-stringed cello while emitting a low, guttural growl, amplified by a horn. This combination of instrument and voice is at once repulsive and magnetic: It is like no music you’ve ever heard, yet you cannot stop listening. After a few moments of auditory assault, Schumann slips into the text before him: “Life, the splendor of a thousand suns all blazing at once….” Dancers crowd in, forming a daisy-chain around me. They begin a rough production line that transports puppets from backstage, down front and center, back around and up through the well above. There, beyond the audience’s vision, the puppets are sent back into the line, creating the illusion that there are untold masses awaiting their turn to be processed.

This line is illuminated at chance intervals by the sweeping beam of the floodlight. Behind me, there is an oversized metronome (built by craftsman Hamburger) that marks mysterious units of time.

As the line comes to a halt, the puppeteers become dancers: walking, falling and crawling upon the naked earth. The light catches their movement and their stillness, as some, like refugees, remain anonymous in their frozen tableaux, waiting for their cue to move.

The dark purgatory taking place is interrupted by the clerk’s bell: Ding! The dancers freeze. “What do you hope your children will accomplish next year?” Silence. “Next.” Ding!

The machine grinds on: Clumps of bodies crash into one another, then collapse, writhing in the dirt. The soundscape becomes increasingly dense and chaotic—the wind, the clackers, the scratch violin, the metronome. Five Bystander puppets rock and sway in their places. The wind blows faster, harder. Groups of dancers knot up and kneel before the Bystanders, where they raise their wriggling fingers skyward. One by one, the Bystanders lean forward. An evening primrose, mounted to each puppet’s chest, blooms. “Oohs!” and “Ahs!” burst out from the audience in response to this simple yet profoundly beautiful transformation.

Schumann blows out the candle. The audience begins to applaud, but ceases abruptly as Schumann holds up an application for citizenship in the Shattered World. “This will be burned and buried in the pine forest.” The audience—which has grown so comfortable in the confines of the theatre—is whisked into the cool Vermont night. A jolly funeral procession, populated by dancers dressed as fancy animals, awaits us. Audience and performers march through the pageant field. A full moon hovers above the pine-tree horizon; a dense blanket of fog hangs over the hills. This exodus is echoed in images printed upon the cloth lanterns that hang in the pine forest.

As we cross the threshold that separates the meadow and the pine thicket, we enter into another world. There, 30 lanterns emit an iridescent glow. Among the dancers and the pines stands Schumann, furiously slicing bread. The actors playing animals slather the sourdough with aioli, and then distribute it to the audience.

A moment later, the only audible sounds are chewing, swallowing, murmurs of pleasure. This act of communal eating, both earthly and cosmic, completes the communion between animal and human; citizen and refugee; past, present and future.

David Dudley is a playwright, performer, and freelance theatre journalist based in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont.