After rehearsal one evening in early August, as The Tallest Tree in the Forest is being readied in New York for its September run at Kansas City Repertory Theatre—to be followed by an October opening at California’s La Jolla Playhouse, and engagements in early 2014 at Washington, D.C.’s Arena Stage and Los Angeles’s Mark Taper Forum—Daniel Beaty and Moisés Kaufman pause to talk about the man they’ve been obsessed with for more than a year, artist and activist Paul Robeson.

Earlier in the day they had met Robeson’s granddaughter. “The level of celebrity he achieved, being able to interact with so many people across the globe—and the fact that he was a scholar and an intellectual as well—all that enabled him to see larger systems,” Beaty posits. The actor and writer, who plays Robeson as well as some 20 other characters in the piece, speaks with a scholarly precision and a tinge of activist fervor.

“That’s it, I love it—larger systems!” Kaufman agrees excitedly. The veteran Venezuelan-born director savors his words while delivering them at a confidently fast clip. “This was a man whose entire project had to do with being an artist. It had to do with race. It had to do with class. It had to do with the colonial people of Africa. It had to do with a certain kind of socialist ideal that he found in Russia. And he was a gigantic star in England, America, Russia—he was really a citizen of the world before that concept was popular, or possible.”

The collaborators, who were strangers before the Tallest Tree project brought them together, are eager to share their insights, biographical and otherwise, about the figure they’re bringing to life onstage. Born in 1898 and raised in Princeton, N.J., by a father who escaped slavery to become a Presbyterian minister, Robeson was one of the first African-Americans to attend Rutgers University, where he excelled at football and was valedictorian of his class. He went on to Columbia University Law School and eventually landed a job at a New York firm, only to be kept out of the courtroom because of his skin color. He quit the job. Disillusionment with the law motivated him to write a letter to Eugene O’Neill that landed him the lead in All God’s Chillun Got Wings, in 1924, launching an acting career that included being the first African-American to play Othello on Broadway.

That was only the beginning for Robeson, who went on to use his fame as a platform to address civil rights and workers’ rights issues.

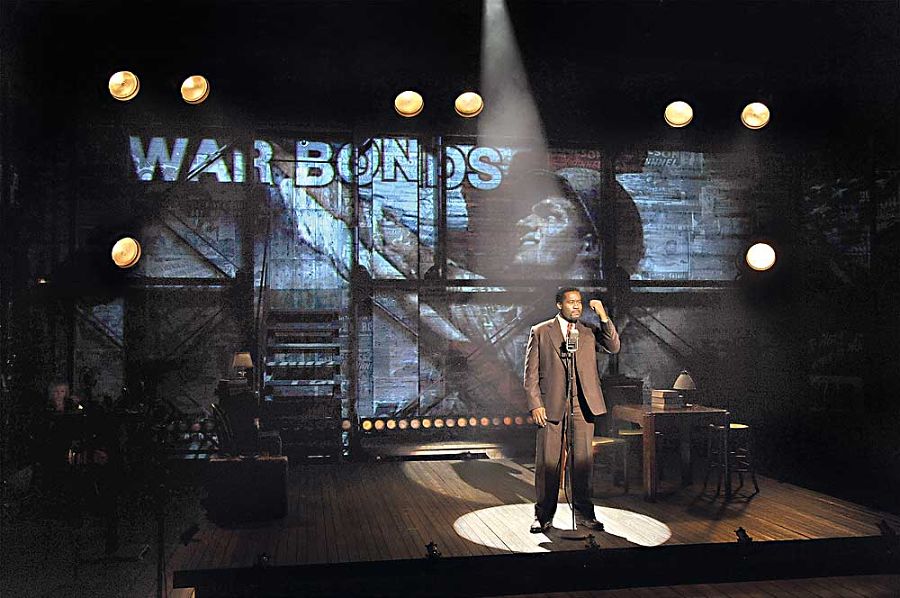

Onstage, Beaty communicates Robeson’s visionary posture eloquently with this line: “My height has enabled me to see what most cannot.” He channels Robeson’s boomy baritone with aplomb, giving the sentence additional gravitas.

For Kaufman, delving into the Robeson story has been an eye-opening experience. Often, he admits, the subjects of potential pieces prove “unworthy” early on in the development process and boredom overtakes him. “What’s thrilling about this,” he avows, “is it always feels like you’re trying to grapple with an intelligence higher than your own.”

Kaufman’s first interaction with Beaty—creator of the widely toured, Obie-winning monologue Emergency and last season’s Off-Broadway solo piece Through the Night—was reading the younger artist’s first draft of Tallest Tree, which he received last year via the playwright-support organization New Dramatists, where Beaty is in residence.

Kaufman was instantly drawn in by Robeson’s story and Beaty’s sharp, succinct dialogue. He also noticed dramatic gaps and problems of structure. As a performer, Beaty told him when they met, “My imagination as an actor is often filling in moments of atmosphere that I don’t necessarily put on the page.” Kaufman, whose own plays include Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde and 33 Variations, could see possibilities in those gaps. Would Beaty be interested in teaming up to work on “a process surrounding the play’s structure?”

“Working with Moisés, I’ve basically written three plays about Robeson,” Beaty says today, more than a year after the pair first connected. “What’s amazing is that all of that material has enriched the moments that were ultimately chosen for this play. There was a breadth to choose from—it became the building not just of a play, but of an immensely complex human being.”

Some of those moments came out of an exercise Kaufman and his laboratory theatre group,Tectonic Theater Project, use in developing new shows—they call it “moment work.” Early on, Tectonic invited Beaty to a retreat in upstate New York. Kaufman asked the actor to think of moments through which Robeson’s life could be told and to perform those for the group. “One of the things I came in with was Robeson trying to take pills after he had had a stroke,” Beaty remembers. That exercise led to fleshing out the contrast between the many different Robesons we see, from early grade school to the final year of his life, while integrating them into a fluid throughline.

Beaty was particularly excited to work with Kaufman because of the emphasis the director places on crafting “visual beats.” I witnessed the creation of one such moment during the rehearsal of a spiritual, “Steal Away,” which Beaty sings early in the show. In the course of the song, Robeson progresses from preadolescence to high school graduation. “I feel like ‘Steal Away’ is keeping a somber tone when we need something more vibrant,” Beaty suggests with concern.

Kaufman counters with an idea: Can Beaty drop his voice down an octave on the last syllable of the line “steal away home,” thereby encapsulating the transition through adolescence in a single note? The tactic works, simultaneously solving the timeline gap while adding vibrancy.

Over sushi a couple of days later, I remind Kaufman about how well his suggestion played. “The big question I’ve posed in 30 years in the theatre is: How does the theatre speak?” he ventures. “What is the theatrical vocabulary? How do you make a piece that’s so uniquely theatrical that it would take a ton of blood, sweat and tears to make it into a movie? Daniel could write a text that says, ‘Then Robeson went from being 11 years old to being 18,’ but I’m interested in narrative that occurs theatrically.”

The fact is that in Beaty, Kaufman has found a richly communicative partner, and there are already hints of future collaborations. “Daniel is not only a virtuosic singer, he’s a virtuosic actor, as you can see—he can play a myriad of characters, each one conveying truth, history and passion. If you’re given a Stradivarius, you know that with a little luck you can construct something beautiful,” Kaufman enthuses.

Back in rehearsal, I watch the frenetic buildup to the show’s Act 1 finale, which is structured around the spiritual “Great Day.” Robeson has just arrived in Moscow with his wife, Essie, at the invitation of filmmakerSergei Eisenstein. They step off the train and are met by hundreds of people of all races. “Look at all the different kinds of faces,” Robeson exclaims to Essie. Eisenstein greets the couple and asks his honored guest to sing for the crowd.

The scene is full of information: Between verses, the couple talks about the three months they spent in Russia, witnessing racial integration and hearing stories from ex-pats who’ve fled discrimination in the States. This is the moment Essie decides she wants to move to Moscow, while Robeson sees the possibility for progress back home and wants to return to be part of it.

“We have to be careful,” Kaufman cautions about the build of the scene. “If we rush, then there are beautiful angels [who join in the song’s chorus] and we’re showing our hand.” The director is bothered in particular by Robeson’s line about fascists: “If we don’t stop them, the world is in great peril.”

“I don’t think he should say this, because it makes him sound super-human,” Kaufman confides to Beaty. “What if we change ‘we’ to ‘America’?” Beaty suggests.

Kaufman takes another tack. “It feels slightly naïve that he’s looking at Russia for two minutes and envisioning this paradise,” the director observes, and then quips, “Of course, he just came out of Germany, so anything would look like a paradise!” They agree to ax the line and continue.

The play spans various countries and several decades, all funneled through Beaty’s performance—in addition to Robeson, Beaty plays the singer’s wife, father, brother, a college football coach, a law firm owner, J. Edgar Hoover, Harry S. Truman, a Jewish poet and a bevy of reporters.

“Too much talk” is a common pitfall of one-man shows, but with Robeson’s story, it’s almost “too much plot”—Act 2 goes on to detail how, after becoming one of the most popular concert singers of all time, Robeson’s political work led to his being investigated by Hoover and the FBI, being called before the HUAC committee and having his passport revoked. “We keep trying to find a coherent narrative that isn’t a seven-part mini-series,” Kaufman says, half-jokingly.

“In Robeson’s fight between being an artist and an activist, he really could not negotiate—he had to be in the trenches,” Kaufman notes. “Some of us believe that being in the arts is a way of being in the trenches, but for Robeson that obviously wasn’t enough.”

For his part, Beaty feels a kinship to Robeson’s activist impulses, and currently splits his time between creating shows and working directly with communities. “I’m launching an initiative that uses storytelling to empower individuals to shift the narratives of their lives,” he says of a program he’s currently implementing at the Children’s Institute in Rochester, N.Y. And even when he’s writing, the larger social tie-in has to be evident. “I can only create a historical story if I feel it has immediate resonance today—the activist part of me finds it necessary.”

Beaty and Kaufman talk as much about the artist’s relationship and responsibility to society as they do about the art itself. “I am curious about how art participates in culture and society,” Kaufman says. “Paul Robeson was a man who, over the course of his life, chose politics over art. You look at someone like Tony Kushner—I’m sure he’s always asking himself when to be an artist and when to be an activist. Daniel and I constantly choose to be artists, and yet we’re telling the story of a person who chose not to.”

Beaty disagrees with that proposition. “As challenged as his professional artistic career became as he went fully into activism, I feel that Robeson remained an artist. He would use his voice as a singer to open people’s emotions to political impulses the same way an artist would. His mastery of language and stage presence would infuse the way he gave a speech.”

Beaty’s fascination with Robeson began when he was training as a classical singer at Yale and started listening to recordings of spirituals Robeson had made. First enthralled by the deep resonance of his voice, Beaty eventually learned about the breadth of Robeson’s accomplishments. Kaufman, in turn, was drawn in by how many of these achievements have been forgotten—“They really managed to erase him from history,” he says—and points out that Robeson’s career is often summed up as the man who sang “Ol’ Man River” in Showboat.

Using the theatre to revisit and reclaim history particularly ignites Kaufman, and it’s at the core of his signature works with Tectonic. “I think the stage is very well set for that kind of journey,” he reasons.

In this journey with Beaty, Kaufman sees his role as “inspiring Daniel to write the play that he wants to write and to flesh out what that play is,” and not to write his own. Nonetheless, the contact high is potent. “Being very close to that creative fire—there are few things in the world like it.”

Arts reporter Christopher Kompanek writes frequently for this magazine.