Approaching the Alabama Shakespeare Festival, you drive through a series of entry points before you get to the building itself. Call it a prep, an amuse-bouche. First, you turn left down Festival Drive, a tree-lined boulevard. The drive opens up into a park, with artfully undulating hills (supposedly designed to mimic the rolling hills of England) and perfectly-trimmed lawns spread out across 250 acres. You round one tree-shaded bend, then another. Suddenly it pops up into view, out of the landscape like a majestic country estate: the red-brick headquarters of ASF, its facade reflected in the glittering lake in front of the building.

The effect is almost eerily calming. The only sounds are the geese in the lake, the birds in the trees and perhaps the putt of a distant tractor. And Shakespeare, it turns out, is everywhere. A full-length statue of him greets you as you enter the lobby, and busts of him keep you company in various sections of the building.

Reality check: Running close alongside this English-styled estate is a busy interstate highway. The peaceful aura is generated by the magic of theatre and landscape design. “For all intents and purposes, we should not be here,” concedes ASF producing artistic director Geoffrey Sherman. “We are way too big for a city of 200,000 people.” That’s only one of the factors that make the existence of ASF so extraordinary.

Besides being the only Equity theatre in the history-steeped, nearly-200-year-old capital city of Montgomery—and the designated state theatre of Alabama—ASF serves a community that includes not only the city (which is surprisingly diverse, with sizable African-American and Korean-American populations); it also reaches audiences in Louisiana, Mississippi and Florida. And despite the recent recession and its attendant drop in audience numbers, ASF retains its long-standing commitment to fostering new work, mainly realized through its vaunted Southern Writers’ Project (SWP) Festival of New Plays, now in its 23rd year. “I tried really hard to not let what was happening to our audience in general affect our commitment to new work,” Sherman attests. “In fact, we probably cut a Shakespeare production to enable us to continue to do new plays.”

ASF’s annual new-play festival, with a varying number of readings each year, is focused on works either from southern writers or devoted to southern themes. True to its mission, 2013 featured plays from a pair of writers born and raised in Alabama (Provenance by Elyzabeth Gregory Wilder and No Mercy: Deconstruction Part 1 by James Bowen); and a native California writer who moved to Alabama (The Wedding Ring, with book and lyrics by Michael C. Vigilant). The final entry was from Kenneth Jones, who is not from the South and does not live there, but whose play was aptly titled Alabama Story. Over the course of a week, the theatre provides actors, a director, a dramaturg and a stage manager to each playwright for rehearsal-room workshops. The event culminates in a weekend of play readings, pre-show talks and post-show talkbacks with audiences. This year’s festival ran May 10–12.

The first show up was from Wilder, a veteran of SWP—2013 was her ninth stint—who grew up in Mobile. Wilder has had three ASF premieres that have stemmed from these readings: Gee’s Bend in 2007, The Furniture of Home in 2009 and The Flag Maker of Market Street in 2011. Wilder’s history with the theatre dates back even further—her first stage role was in Peter Pan at ASF when she was 15. No wonder she considers it her artistic home. “SWP is a great place to succeed and a safe place to fail,” Wilder reasons during the pre-talk for Provenance. “There’s not a big industry presence here—you can really focus on the work and not on whether or not a theatre’s going to pick your play up for production. For me, it’s just a really safe place to try new things.” The play is about a woman who has a bucket list of 100 first editions to read before she dies. When she arrives at the library where the final book on her list is supposed to be held, she discovers that it is missing, and becomes friends with the taciturn librarian.

ASF associate director Nancy Rominger, who heads SWP and who also directed The Wedding Ring over the weekend, reads hundreds of submissions (some unsolicited) for the festival (“Please don’t make me count!” she exclaims). What she is looking for in the four scripts are pieces with development potential. “It should be a good fit for us, but we should have something to give the playwright as well,” she notes. Sometimes the pieces chosen are not finished and, as in the case of Provenance, the first draft is completed at the festival.

And ASF, unlike other sponsoring organizations, does not make a commitment to produce any of the workshopped plays, so there is little sense of competition between the works. All the same, since Sherman took over the theatre eight years ago (bringing Rominger with him), around 50 percent of the plays that have come through the festival have been fully produced at ASF.

Rominger prefers a light touch in developing a play and readying it for production. “Like children, they develop in their own ways and sometimes it takes many years for them to realize their potential,” she says. “At other times it’s a very quick process. And sometimes, a play develops well, but it’s not right for us. Then it becomes a matter of trying to help the playwright find the perfect theatre.”

The second play of the weekend, No Mercy by James Bowen, was read last year as well. And Sherman is willing to put in still more time developing it. “It’s all about process,” says the playwright, who acts regularly in ASF productions and holds a resident-playwright post at the theatre. “If on Thursday, I decided that my Act 2 was incomprehensible, we could have just read Act 1.”

No Mercy, a period drama set in 1902, begins with two African-American men taking shelter in an inn, where they meet a third man who is waiting for his lover. The complicated backstory of the couple’s relationship forms the crux of the play, whose themes touch upon the role of African Americans in the South during Reconstruction.

“We’ve been convinced that the South is the most evil, horrible place you can go in that time period,” Bowen reflects. “From all I’ve now learned, I don’t believe that’s necessarily so.” The artists and audience members of ASF are well aware of the stereotypes that the rest of the country has about their region. “Actors do this as well. If you’re going to play someone stupid, the first thing you do is give them a southern accent,” Bowen adds with a wry grin.

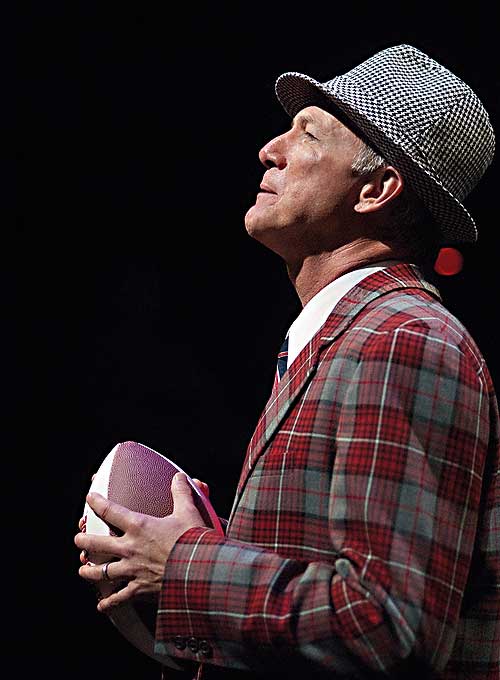

The third play of the weekend, The Wedding Ring, a musical with book and lyrics by Vigilant and music by Gerald V. Castle, detailed the relationship between a man and woman from meeting to marriage to divorce, with a boxing ring as a framing device. Vigilant is ASF’s chief operating officer; he also wrote Bear Country, about University of Alabama football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant, read at SWP in 2008 and premiered in 2009, where it became the biggest selling play in ASF history.

“What is so important about the Southern Writers’ Project is these are stories from the South, exported from Alabama. So along with football, lumber and golf courses, there are also these plays going out and getting published,” Vigilant opines. “In a place where education suffers, and, to some extent, so does culture, ASF is a beacon of art, making sure that assistance is given to help these stories be told well and then sent out to other places.”

The success of Bear Country and other SWP plays indicates a hunger in the community for locally grown stories about the South. So for Kenneth Jones, a New Yorker, the standing ovation of the very first reading of his play Alabama Story was especially gratifying. The play takes a whimsical look at the real-life controversy about the children’s book The Rabbits’ Wedding by Garth Williams, which was forced off Montgomery library shelves in 1959 because it was interpreted as supporting integration.

“I wanted it to be steeped in the Deep South, to be as authentic as possible without being a cliché,” Jones explains post-reading on Sunday, after a week of staying up until 3 a.m. rewriting. The play was finally completed on Friday. “I wanted to see if it passed some sort of historical muster.” Jones plans to take Alabama Story back with him to New York City for further development. “I now want to hear reactions beyond those of the local audience, to see what’s universal about it.”

That motive is appropriate, even welcomed, since Sherman and Rominger frequently use the phrase “geo-specific theatre”—works that stem from a particular region that speak not only to the people of that region, but become universal. And this specificity—in a region where there are very few places local writers can go to develop their work—is what makes SWP special, according to Rominger. “We give a voice to southern playwrights and southern stories that might not actually ever be heard, and we bring them to light. There’s a wonderful history of gorgeous southern storytelling, from Faulkner on, that we can’t lose.”

Toward the end of Bowen’s No Mercy, the character Clanton Grant, a journalist, says: “I’ve never seen the South, sir. Mr. Lincoln used to say that without the South, we have no country. I’d like to get to know it better.” The Alabama Shakespeare Festival and its Southern Writers’ Project are eager to make the introduction.