At just 39, and with barely a decade in his field, Rajiv Joseph has become one of the most-produced playwrights in the U.S. But unlike many writers in that company, his frequency of production is not on the strength of any single hit play—certainly not his Broadway breakthrough, Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo. That 2010 Pulitzer finalist—a dark, pungent magic-realist fantasia set during the early days of the Iraq War, with a large-ish multiethnic cast, a thornily ambivalent tone, and free-ranging design demands—has been a tougher sell than, say, Clybourne Park or Good People.

That’s not the only way that Joseph’s career has defied the norm. For it wasn’t Bengal Tiger on Broadway in the spring of 2011—or the nearly simultaneous Off-Broadway mounting, at Second Stage Theatre, of his Gruesome Playground Injuries, a two-character study of pain as an emotional bond (published in AT, April ’11)—that put Joseph on the map as a voice to be reckoned with. In fact, both Bengal Tiger and Gruesome had originated at regional theatres (Center Theatre Group of L.A. and Houston’s Alley Theatre, respectively), and they were just two among a seeming flotilla of Joseph plays that popped up all over theatre season schedules in early 2011. There was the tense racial-profiling two-hander The North Pool at Palo Alto, Calif.’s TheatreWorks in 2011 (which only made its New York bow this past spring at the Vineyard Theatre); then came the apocalyptic art-world mystery The Monster at the Door at the Alley (in May of the same year). Those followed close behind a few earlier New York productions: All This Intimacy and Animals Out of Paper at Second Stage, and Huck and Holden at Cherry Lane Theatre.

In the years since this uncanny, seemingly all-at-once national emergence, Joseph did two seasons as a staff writer on the Showtime series “Nurse Jackie,” cowrote and sold a film script about football, and got another batch of plays ready for production. The Lake Effect, a cross-racial family drama co-commissioned by Chicago’s Silk Road Rising and New Brunswick, N.J.’s Crossroads Theatre Company, ran in April and May at Silk Road. In the fall he worked at New York’s Lark Play Development Center on a new two-character play called Guards at the Taj, about two sentries at the Taj Mahal in the 1600s. He has a long-gestating commission from South Coast Repertory in Costa Mesa, Calif.

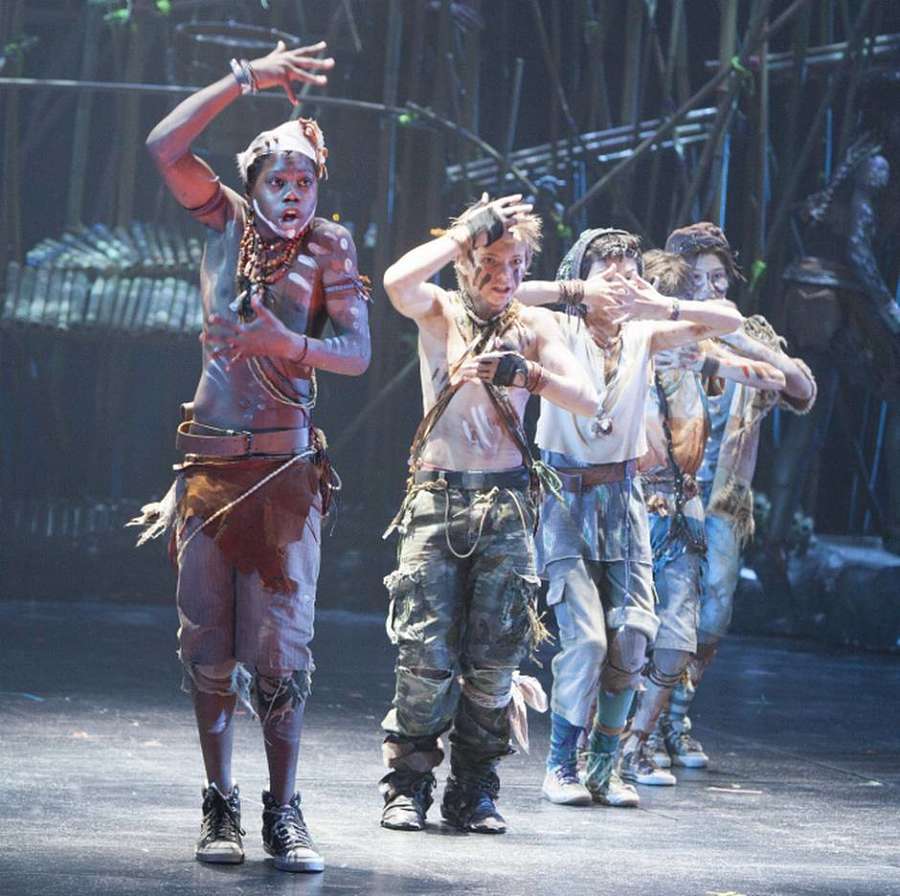

The occasion of his recent sitdown with American Theatre, though, is a new musical based on the Peter Pan story called Fly, which runs at the Dallas Theater Center July 2–Aug. 18, with its eye clearly on Broadway. The producer is Jeffrey Seller (Rent, In the Heights, Avenue Q), who is also making his directing debut with the show; Joseph wrote the book, as well as the lyrics (with the help of Kirsten Childs, of The Bubbly Black Girl Sheds Her Chameleon Skin fame). Bill Sherman did the music, Andy Blankenbuehler (Bring It On) is the choreographer, and Pichon Baldinu of De La Guarda is doing the flying effects.

In other words: Get ready for another Rajiv Joseph wave.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: You’ve created so many regional relationships all over, rather than launching your career with one big Broadway hit.

RAJIV JOSEPH: Well, I started in New York with Huck and Holden and All This Intimacy, but my more well-known plays all started out of town: In L.A., Houston, Palo Alto—and now Fly in Dallas. I often like the regional productions better than the New York ones.

But were you happy with the Broadway production of Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo?

I really was. It’s easy to say, but it was my favorite production—it was the only production I could watch over and over again without getting uncomfortable. It was a thrill. Those guys had been doing it for three years together, with [director] Moisés Kaufman and the same design team.

I liked that production, too, but I can see why it was a challenge for audiences.

That’s because you’re casting a wider net on Broadway—it’s there halfway for tourists, so it’s not like the normal theatregoing audience. By and large people liked it, unless they went in thinking they were seeing a Robin Williams comedy show—especially when he got shot and killed in the first scene.

How did that play come to him?

His manager’s wife saw it in L.A. and flipped over it and told him about it. Then when the producers were trying to think of someone to go for, he was the first person we officially went after. He has this history, you know, of working with veterans—he’s gone to Iraq and Afghanistan on USO tours. The plight of the veterans is a cause that is very dear to him, so he had an investment in the material.

That’s interesting, because the American soldier characters don’t come off that well in the play.

You know, one of the problems with starting this off with a great director like Moisés and the great actors I had is that I often don’t see some of the weaker parts of the text. And I’ve seen productions of it since then where the character of Kev just comes off as cartoonish, and I wish I had written it differently. I see it now but I never saw it before, because Brad Fleischer is a great actor and Moisés is a great director, and they never played it for that cartoonish quality. But what can you do? It’s done and gone.

I remember when you first emerged that your plays seemed to oscillate in scale, between big and small. Do you still feel that back-and-forth in your work?

I do. But every play fluctuates as you enter it. Sometimes you know immediately what it’s going to be. I just completed another two-person play that I never doubted was a two-person play, and I wrote it pretty quickly. But another play I’m working on has been four characters for a while, and now I’ve just realized it has to be five. The North Pool has gone up and down; it used to be six characters, then three, and then two.

It’s like you’re laying off characters.

Exactly. Each process is different. But I also find that I try to make it active with as small cast as can be, for no other reason than I am trying to make sure that there’s nothing extraneous.

Not because of commercial con춖iderations?

Not at this point; I don’t have a problem getting people to read my plays. Initially it was probably a smart thing to not have a play with 11 characters in it, but then, I also think that’s really hard—I can’t imagine writing a play with 11 characters, outside of a musical. But as I begin to write for TV and film, it’s fun to go back to theatre and think of all the things you can do that you can’t do on-screen.

That’s interesting. Some might think that after being able to put the camera anywhere, you would feel constrained by theatre.

I mean that you’re not constrained to a formula. And as I’m writing more movies, I feel less of a desire to write naturalistic plays. I do my naturalism in movies. If I’m going to write a play, I want to exercise those other parts of my brain that are like, “Let’s have fun with this, let’s go to some crazy places, and not worry about the kitchen sink of it all.”

Speaking of fantastic places, tell me about Fly. How did you get on board?

Jeffrey Seller, the producer, is the creative force behind it; it was his idea. He came out to L.A. to see Bengal Tiger at the Kirk Douglas Theatre and we had a long lunch together and talked about our ideas for a musical about Peter Pan, which was my favorite story growing up. And even though I did love the original Mary Martin musical, I always had a problem that it was a woman playing Peter Pan. So my first thing was: It has to be a boy.

What we’re doing is based more directly on the novel Peter Pan, and there’s a real dark undercurrent to it that is seldom explored in any of the past dramatic incarnations of the story. We’re trying to bring that into it while still making family-friendly entertainment.

I have to ask, what are you doing about the Native American stereotypes?

We don’t have the Indians. We do have this beautiful ensemble of female dancers who kind of represent the island—they’re like the trees, and they’re kind of omnipresent. They dance and they back up the children, and they also are going to be the ones who fly the kids. We’re not going to have invisible wires; you’ll be seeing ropes and you’ll see the kids get harnessed and then hoisted up in the air by those women.

Did you look at a lot of musicals and study the form?

I did. Before I moved to New York, before I decided to be a playwright, really the only theatre I’d seen was musicals. I really liked them, and I inadvertently studied them. I used to work as a maintenance man at a theatre in the summers in Cleveland—Cain Park. It was my job to wait till the thing was done, so I would sit and watch Into the Woods every single night for the whole summer. And I realized with Fly that I was hearkening back to my knowledge of these musicals I’d seen not once, not twice, but like 35 times.

And weren’t you in Nine as a kid?

Yeah, same place.

That’s a pretty sexy show to do as a kid.

Oh my God! Even at the age of 11, I was like, “Wow. This is the life for me.”

Sondheim talks about how you should have a specific idea for every moment, for every choice you make.

I can see him thinking like that, he’s so particular and intense. His books on writing musicals—have you read them? I find them amazing and exhausting. I’ve been reading them as an actual textbook as I’ve started to write lyrics. I can read two pages at a time, and then I have to shut it.

You initially wanted to be a novelist, and indeed, playwrights often start off as other kinds of writers, and the way they discover they’re playwrights often has something to do with dialogue.

Definitely, using dialogue to tell the story, and not having to worry about the description, or even the accuracy of things, you know? If I wrote a novel about Iraq, I would have to really feel like I knew the ins and outs of it, but to write a scene about Iraq, you are limited to, and blessedly hemmed in by, your character’s limitations. So if I’m writing from the perspective of Kev, I’m just writing about an American guy in Iraq who doesn’t know shit, and can speak accordingly. And I don’t have to explain the reality around him.

Obviously, you had to do some research for the character of Uday Hussein, one of Saddam’s sons, who’s a major character.

Oh, I did exhaustive research for the play, but I did the kind of research that I like—I got into a very intuitive search for connectivity between tigers, spirituality, the historic/spiritual history of the Baghdad region, topiary, ghosts and lepers. But I didn’t have to worry about getting certain descriptive details to a T.

You’ve said, I think, that though you’re part Indian, you don’t always write from an Indian or Indian-American point of view.

I don’t always think that way. When it happens, it happens, and often if I’m struggling with something, imagining somebody as a different race, or gender, even, snaps it into focus. That happened with Animals Out of Paper; I didn’t set out to write an Indian character in that play, and then it turned out, as soon as I imagined this kid as who he was, it couldn’t be any other way.

Indian characters aren’t your default.

Not necessarily. The story kind of dictates itself. Like, Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo wasn’t going to have any Indian characters in it. Gruesome is kind of colorblind, generally speaking. But then Guards at the Taj, they’re two Indian characters; but they’re from the 1600s, and they’re part of the Mughal Empire, so they’re also kind of like Persian and Kazakhstani, so there’s any blend of what they could be in this play. It’s not really a play about India so much as it is a play about this friendship.

Your dad is from South India. Do you visit India often?

I go there probably every 18 months. My grandmother’s there; she’s very old. I have friends there now—theatre friends from New York who are Indian that moved back to India, so when I go to Bombay I see them. I’ve got a pretty nice network of people in India now.

Has it changed a lot?

Hugely—so much. When I was a kid, we would pack our bags with stuff to bring them—they wanted, you know, Velveeta cheese. There was so much you could not buy there because the markets were closed; it was a totally closed socialist society. And then they opened, and on top of India opening, India became one of the bigger hotspots for technology. So many of my Indian friends and my Indian relatives have moved back to India because there’s better work; they’re not just doing it because they want to go home. They’re doing it for the same reasons that my dad came to America; he was like, “There’s a better job for me there.”

Has Bengal Tiger played there?

No, but I went to teach at NYU’s Abu Dhabi campus, and they did a reading of Bengal Tiger there and I taught a master class. There were 13 students and most of them were women, and they all wanted to be in the reading. I was like, “All right, well, there are eight roles, most of them are men. But a couple of you actually speak Arabic, so I’m going to give you the Arabic-speaking parts.” And then I cast the men in the men’s roles and I split the tiger between five women, and so every monologue was a different woman reading the tiger. It was cool.