“Urk!” “Huff huff.” “Sshing!” “Fwoosh.” “Fwooom !” “Twackk!”

William Shakespeare is credited with inventing countless words and phrases that the stuff of our everyday speech is made on. But I daresay that the words which appear above—if words they be—are not of the Bard’s making. Yet I just read them in Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet. That is, in the graphic novels of those plays from Capstone Press, where they’re employed like the “pows” and “bams” of TV’s “Batman.”

You might think that graphic novels of Shakespeare are a freak novelty, but in fact they’re an entire subgenre. I’ve amassed an incomplete selection of these works that stands some two feet high—a mix of comic books, paperbacks and hardcovers. And I know I’m only scratching the surface. (By way of example, Oxford University Press has a series that would apparently be contraband in this country; in North America, only Canadians can purchase it. No kidding.)

I plunged into this array of adapted Shakespeare as a fan of the plays but no expert, and as a novice in the world of comics and graphic novels. My interest emerged from my own experience, at age eight or nine, during Nixon’s first term, of reading The Iliad and A Tale of Two Cities, not in their original versions, but via the series of comic books called Classics Illustrated. Although they ceased publication in 1962, my brother and I scavenged barely vintage copies from paper drives and tag sales and secured them in a tin breadbox (also found curbside); we would withdraw them from their cask on a narrow loft in our garage to read about Sydney Carton and Helen of Troy. Why we required an aerie for this I don’t know—our schoolteacher mother wasn’t likely to have objected. As a result, I am no snob when it comes to this form, but rather a childhood fan looking to see how it has developed.

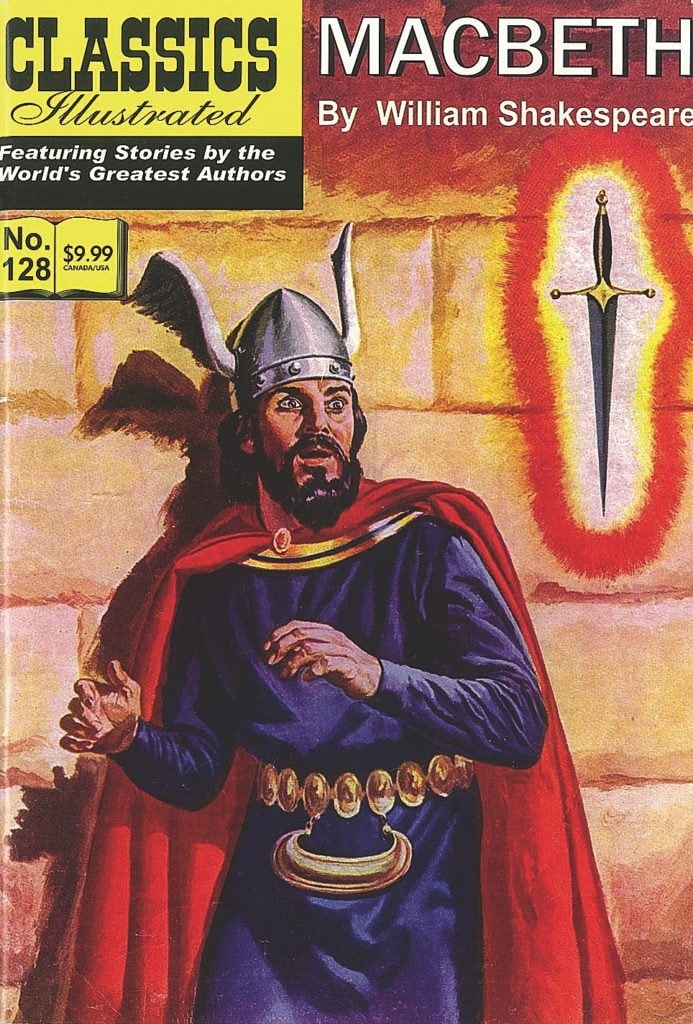

Remarkably, the original Classics Illustrated titles have been reissued, so I’m now able to see how Shakespeare was handled back in the day. There’s a mighty startled Macbeth on one cover, wearing a winged headpiece in a comic which first appeared in 1955 (and which now costs $9.99 as a reprint, startling me as well), staring at a floating dagger enveloped in a flaming nimbus that evokes the burning bush. The interior art, from the years before Jack Kirby, recalls Prince Valiant, but the language, albeit edited, is unmistakably rooted in Shakespeare (then again, the Norse comic hero Thor was derided in the film The Avengers as “Shakespeare in the Park” for his faux classical aspect). Rather than dumbing down the text too much, words like “thane” and “raveled” are footnoted. What’s most striking, looking at an original Classics Illustrated book after so many years, is that while it is all too obviously a product of another time, it doesn’t seem over-simplified for children; I imagine that those of us who read them once upon a time felt pretty smart without feeling pandered to.

Remarkably, the original Classics Illustrated titles have been reissued, so I’m now able to see how Shakespeare was handled back in the day. There’s a mighty startled Macbeth on one cover, wearing a winged headpiece in a comic which first appeared in 1955 (and which now costs $9.99 as a reprint, startling me as well), staring at a floating dagger enveloped in a flaming nimbus that evokes the burning bush. The interior art, from the years before Jack Kirby, recalls Prince Valiant, but the language, albeit edited, is unmistakably rooted in Shakespeare (then again, the Norse comic hero Thor was derided in the film The Avengers as “Shakespeare in the Park” for his faux classical aspect). Rather than dumbing down the text too much, words like “thane” and “raveled” are footnoted. What’s most striking, looking at an original Classics Illustrated book after so many years, is that while it is all too obviously a product of another time, it doesn’t seem over-simplified for children; I imagine that those of us who read them once upon a time felt pretty smart without feeling pandered to.

The modern era, so far as I discovered, kicked off in the ’80s with Workman Publishing’s rather conventional Macbeth, illustrated by Oscar Zarate; its first notable creative mark came with what Workman billed as Ian Pollock’s Illustrated

King Lear, Complete and Unabridged. Owing more to Ralph Steadman and Gerald Scarfe than to DC or Marvel, this was a Lear of grotesques. I suspect it would send a purist running away quickly, despite fidelity to the original text. Applying the language of theatre, Pollock’s book is visually avant-garde, even almost three decades on.

Indeed, it was the language of theatre that came to mind most often as I traipsed through these recent volumes; primarily dating from the past decade or so, they mostly adopt the visual style of superhero comics or Japanese manga (there are three competing series of Manga Shakespeare). As a result, they resemble nothing so much as storyboards for intricate movies. Because most stay reasonably faithful to the text, the words often crowd the frames; they break loose when they portray action that would be blocked on stage, or offer us a normally offstage vision (we see the dead Ophelia just as the text describes her). Wiley’s manga edition of Julius Caesar is at its strongest as “silent” panels overtake the text in the final pages.

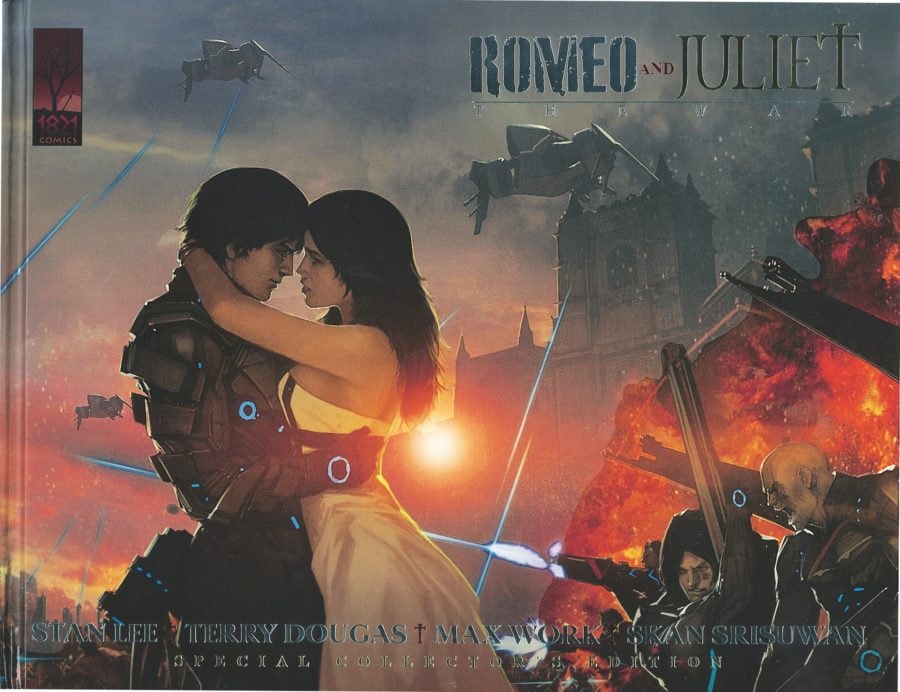

The storyboard parallel is most pronounced in one of the newest entries, the sci-fi epic Romeo and Juliet: The War, credited to four creators, including the august Stan Lee. The horizontal, hardcover, full-color book resembles one of those profusely illustrated tomes on The Art of Star Wars, created to sate the desires of die-hard fans. But don’t go looking for faithful language here: In their first meeting at the masquerade, our futuristic Romeo propositions Juliet with, “Maybe one

day I can see you without your costume.”

Though less visually epic, there’s also a scifi Macbeth graphic novel from Puffin that acknowledges its effort to blend Shakespeare with the works of authors Larry Niven and Anne McCaffrey: If starting the story of the Thane of Glamis and Cawdor with him astride a dragon in the year “Stardate: 1040” sets your heart racing, this is your book.

A futuristic Romeo and Juliet may still startle today’s audiences/readers, long after the tale of star-crossed lovers has been adapted, manipulated, parodied and plagiarized in every possible permutation. But that’s where these many treatments of Shakespeare serve another purpose: to offer new interpretations in different settings and time periods without the expense of theatrical production. To be sure, the most explicitly educational books hew close to a traditional line, as evidenced by the series from Graphic Planet and Campfire Classics: Simon Greaves’s books from the Shakespeare Comic Book Company even subordinate image to text, offering side-by-side original text and simplified modern speech, as if subtitled. The books from Classical Comics, while drawn in superhero glory for the most part (though their A Midsummer Night’s Dream is appropriately pastoral), come in three “flavors” for each title: original text, plain text and quick text, suited to every entertainment or pedagogical need.

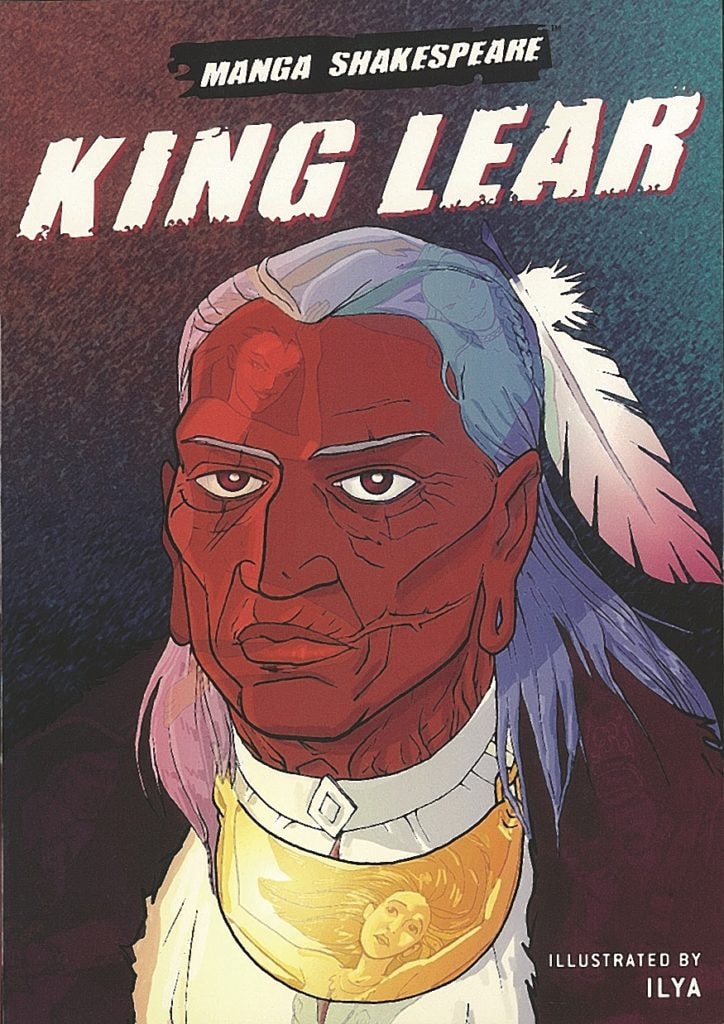

Emerging from this collection as among the most intriguing are the books that look least like conventional comics and instead adopt designs that play with visual style in new ways. Hamlet and Macbeth from “No Fear Shakespeare” bear a passing resemblance to the works of Art Spiegelman or Marjane Satrapi, while the Amulet Books Manga Shakespeare series offers the greatest variety—from an anime-inflected Much Ado About Nothing, to a roughly sketched, chiaroscuro Julius Caesar that eschews any shades of gray, to their pièce de résistance (of those I’ve seen): a Native-American King Lear. You may find it jarring to see an Indian chieftain declaring, “Attend the Lords of France and Burgundy, Gloucester” and have trouble with a Cordelia who echoes Disney’s Pocahontas, but there’s no denying that a powerful imagination has been brought to bear.

Emerging from this collection as among the most intriguing are the books that look least like conventional comics and instead adopt designs that play with visual style in new ways. Hamlet and Macbeth from “No Fear Shakespeare” bear a passing resemblance to the works of Art Spiegelman or Marjane Satrapi, while the Amulet Books Manga Shakespeare series offers the greatest variety—from an anime-inflected Much Ado About Nothing, to a roughly sketched, chiaroscuro Julius Caesar that eschews any shades of gray, to their pièce de résistance (of those I’ve seen): a Native-American King Lear. You may find it jarring to see an Indian chieftain declaring, “Attend the Lords of France and Burgundy, Gloucester” and have trouble with a Cordelia who echoes Disney’s Pocahontas, but there’s no denying that a powerful imagination has been brought to bear.

Indeed, the play King Lear seems to have inspired the widest visual variety; in addition to Pollock’s early entry and the Amulet book illustrated by the one-named Ilya, Gareth Hinds’s stylistically eccentric version for Candlewick Press features typeset text that at times loops around water-colored images—but there’s no mistaking the impact of Cordelia’s death when the color drains from the page.

Although the artistic and textual approaches among these many volumes vary widely, it’s fairly safe to assume that at their root, all are efforts to make Shakespeare more approachable for the novice, most likely pre-college students. The importance of the standard middle school and high school curriculum is surely the reason for the plethora of graphic Hamlets, Tempests, Romeo and Juliets and Midsummers. I found no Titus Andronicus or Timon of Athens in my pursuits; they proved even rarer than stage productions of those plays. The volumes that attempted a more mass-market sales spin can run afoul of their own educational mission; for example, the folks at Spark Publishing, responsible for the “No Fear” series, apparently take an awfully benevolent view of Richard III, as they declare

Macbeth to be “the only Shakespeare play with a villain for its hero.”

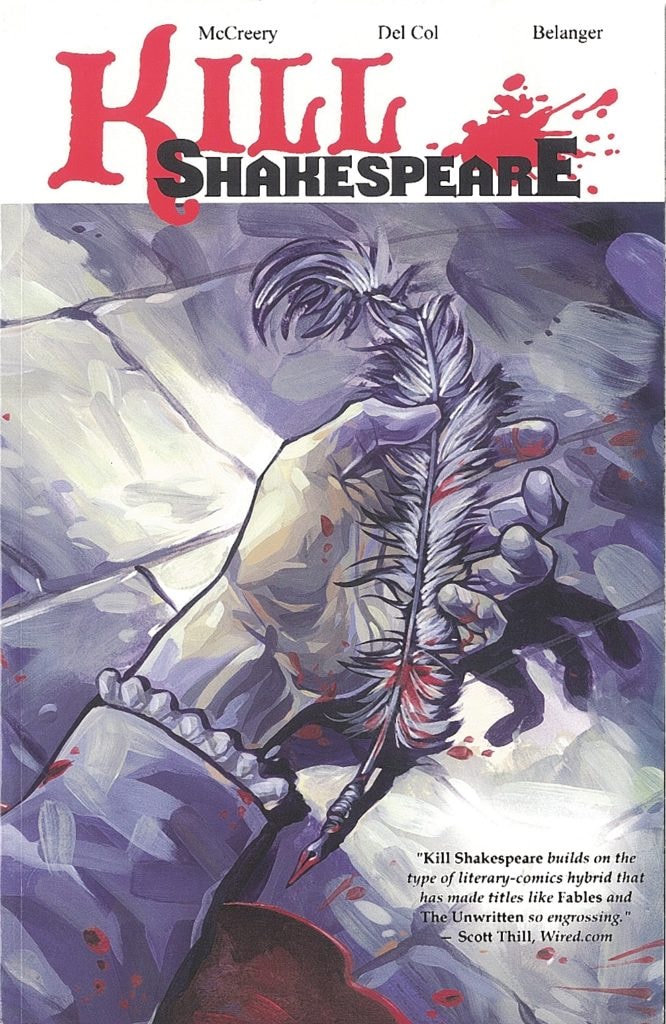

Depth of Shakespearean knowledge is evident among the creators of perhaps the most innovative of graphic-novel Shakespeares. The authors and artists of the Kill Shakespeare series from IDW Publishing have abandoned any singular work and instead dreamed up a massive Shakespearean mashup in which Hamlet and Juliet join forces to battle against such villains as Richard III and Iago, who seek to vanquish (in the words of their marketing copy) “a reclusive wizard named William Shakespeare.” While the characters are familiar, their quest is wholly new, and their challenge transforms even those we think we know well; the surviving Juliet, still

Depth of Shakespearean knowledge is evident among the creators of perhaps the most innovative of graphic-novel Shakespeares. The authors and artists of the Kill Shakespeare series from IDW Publishing have abandoned any singular work and instead dreamed up a massive Shakespearean mashup in which Hamlet and Juliet join forces to battle against such villains as Richard III and Iago, who seek to vanquish (in the words of their marketing copy) “a reclusive wizard named William Shakespeare.” While the characters are familiar, their quest is wholly new, and their challenge transforms even those we think we know well; the surviving Juliet, still

mourning Romeo, has taken on traits more typically associated with Joan of Arc.

For those steeped in the world of graphic novels, Kill Shakespeare is the Elizabethan equivalent of Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen series, or perhaps Jasper Fforde’s (unillustrated) novel Something Rotten, although Kill is unmistakably and distinctively its own achievement. Having only finished Volume 1 of the series (Volume 2 is available, while Volume 3 is in the works), I’m already eager to find out if the scantily clad vixen who beckons Iago on the final page is, as I suspect, the formidable Lady Macbeth; Classics Illustrated never looked like this (nor was it serialized).

Coming full circle, it’s worth noting that the Classics Illustrated trademark has been revived, for a new graphic novel series, by the Papercutz imprint. And while newly drawn and edited, these share a common trait with their predecessor of 50 years ago—they conclude with the same message: “Now that you have read the Classics Illustrated Edition, don’t miss the added enjoyment of reading the original, obtainable at your school or public library.” It’s a message that might well conclude every graphic novel version of Shakespeare—although perhaps it’s unnecessary, since these adaptations, if successful, make their own case for the plays. On the other hand, I never did read The Iliad, did I?

Arts professional Howard Sherman has previously served as executive director of the American Theatre Wing and the Eugene O’Neill Theatre Center.